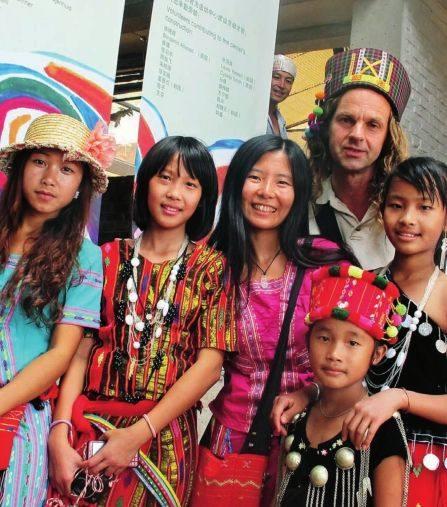

The Lustigs: Share Love with Jingpo Children

By LI YANG

I used to work as a legal counsel for a transnational infor- mation technology company. I quit in 2005 and became an environmental protection volunteer for the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Over the past eight years I have worked with public welfare institutions such as the WWF and the U.S.-based Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in communications and promotions work, with the aim of building a bridge between environmental protection experts, media and the general public.

In 2009, I opened a new chapter of my dream career. During the Spring Festival that year, I visited J ingpo Mountain Village, home to people of the J ingpo ethnic group, on the border of Yunnan Province and Myanmar. My husband Anton had made many trips to the village before; I was joining him for the first time.

I fell in love with the natural environment around the mountainous village, and with the genuine smiles on the faces of its people. The cultural and artistic legacy of the J ingpo is truly unique. It is manifested in many ways, among them singing. We attended the Munao Songfest, a grand annual J ingpo festival during which thousands of people gather to sing and dance for several days.

My husband, whose full name is Anton Lustig, is the worlds foremost expert on the J ingpo people and their language. He has been visiting the village for decades. He is surely the only non-Chinese person to speak fluent Zaiwa, the regions Jingpo dialect. Such is Antons commitment to the ethnic group that he often jokes he is actually a local, but was accidentally born in the Netherlands.

Anton earned a doctors degree in Sino-Tibetan studies at Leiden University and has been engaged in linguistic and cultural research in the Dehong Dai and J ingpo Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province since 1991. He was the first scholar to comprehensively and systematically record and describe the Zaiwa language. He published the 1,700-page Zaiwa Language Grammar and Vocabulary, which has become the standard reference on Zaiwa for institutes of higher learning and language researchers around the world.

Anton finished his studies and research a long time ago. But he still finds it hard to part with the place to which he devoted 20 of his best years. “I always feel like I should be doing something for the area – its my second home,” says Anton.

And so, Anton and I ended up settling down in Dehong in J une 2012. In the very beginning we just wanted to lead an ordinary life there, which for us meant painting, writing and teaching local children. We traveled between Beijing and Dehong. Some of our friends later came out and helped us with teaching.

The J ingpo children with whom we have extensive contact live in beautiful mountain surrounds. But the prefectures challenges, chief among which is drug abuse, adversely affect the younger generations. J ingpo youth are talented, but often are forced to drop out of school due to the poverty born of endemic social problems. Simply donating materials and money, or even offering teaching support, is not enough to give the children the chance at life they deserve.

Its not just young children dropping out of school. Many high school students also quit as they become hesitant about their future prospects. We sensed we needed to do something, which led us to establish a professional public welfare institute. We called it“Banyan Roots.”

Why the name “Banyan Roots”? J ust imagine a big banyan tree. Its roots grow deep into the soil, absorbing nutrition and providing sustenance to the tree trunk and dense foliage. As in many places across Asia, the banyan tree is regarded as sacred by the J ingpo people. In J ingpo villages, banyan trees often serve as meeting places for public gatherings.

We combine local culture in our language and art classes, helping J ingpo children understand their own roots, get to know themselves, widen their world view, raise their interest in studying and build up their self-confidence. Through various subjects such as traditional puppet plays, photography and painting, children are encouraged to express themselves, boldly pursue their dreams and form a positive and optimistic outlook while facing the damaging influences of evils like drug addiction.

Through five years of efforts, our institution has launched education projects in such places as Panying Elementary School, where we enjoyed a fruitful year. We received much positive feedback from pupils.

On May 26, 2013, our Banyan Roots Childrens Activity Center, a building that combines traditional J ingpo architecture precepts with modern architectural elements was finally opened in the J ingpo Mountain Village in Dehong. The center offers free culture and art classes to children. To mark the opening we held the “Entering the New House” ceremony, a traditional J ingpo event. The whole community participated in preparations for the ceremony, which included offering a token sacrifice to the Mountain God, dinner, singing and dancing and a childrens painting exhibition. Over 200 locals from the village – and others from nearby towns – attended the ceremony.

Anton and I have now well and truly quit our jobs in Beijing. We are totally devoted to the development of Banyan Roots. Although we have had to take part-time jobs in the evening to support the project and pay back the money we owe on the activity center building, it is comforting to know that our efforts are directly benefiting the Jingpo children. We are living the dream.