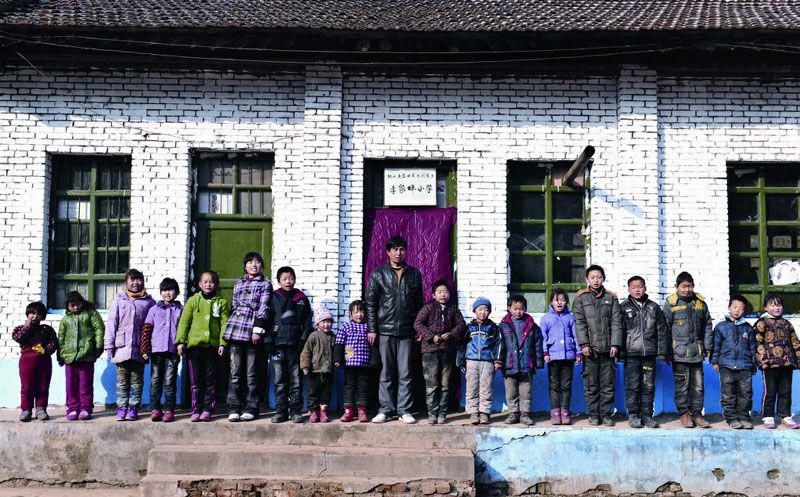

Care and Concern for Left-behind Children

Nowdays large numbers of young rural residents move to cities in expectations of better work opportunities. Statistics show that there are 230 million migrant workers in China – a figure that implies a huge population of so-called left-behind children in rural areas. Left-behind children are those that fend for themselves while either one or both of their parents live and work in cities. The Study on Left-behind Children in Rural China released by the All-China Womens Federation shows that there are more than 58 million left-behind children under 18 years old in rural areas, of whom 40 million or more are under 14. Around one third have been living apart from their parents for more than five years. Of these, 52.86 percent are estranged from both parents, 47.14 percent are in a single parent arrangement and 48.35 percent live with their grandparents.

For left-behind children, living in a standard family with both parents is an impossible dream. People from all walks around the country have done their utmost to help those lone-living kids.

Help from civil society

Twelve-year-old Cao Chengwei lives in Shangdonglin Village, Xipeng Town in Chongqing Municipality. At the end of the school day he goes to the villages Happy Home for Leftbehind Children to have a video chat with his mom, who works in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Caos parents left home to find work in the city when he was just five years old. He has since lived with his grandparents, now in their 70s. The boy sees his parents only twice a year.

The Happy Home for Left-behind Children receives a dozen or so children like Cao Chengwei each day after school. The home consists of a video chatting room, a psychological consulting room, a reading room and a games room. Around 20 college-graduate village officials work in shifts at the home helping children with their homework or just playing with them.

There are more than 1,100 left-behind children in Xipeng Town, and every village in the town has set up its own Happy Home. Workers at the homes organize activities that help the kids to grow up happy and healthy. The village committee has also selected cadres to serve as substitute parents for these children. They are responsible for the kids daily life and studies, but most of all for giving them a sense of parental love in their real parentsabsence.

Assistance from civil society for these children is becoming the prevailing trend in Chongqing. There are 1.07 million left-behind children in the southwestern municipality, representing 26.49 percent of the total from kindergarten to junior middle school ages. Absence of parental care and over-indulgence from grandparents have brought about certain character defects and anti-social behavior in many children that are serious causes of concern to both families and schools.

The Chongqing municipal government has acted to remedy the situation by expanding and improving childcare facilities and services. This includes allocating substitute parents, setting up boarding schools, and entrusting lone-living minors to the custody of their relatives. Over the past few years, the city has built 1,813 outof-school childcare institutions and 980 childrens homes in rural communities. Around 80,000 substitute parents have also been selected to help children on an individual basis during after-school hours. So far 2,200 video chatting rooms have been set up in 1,700 or more schools in Chongqing, and 10,000 phone landlines installed in more than 3,000 schools, making it convenient for children to maintain contact with their parents living outside of the region. The government hopes these measures will to some extent ease the woes of left-behind children.

Government initiatives for all rural schoolchildren, such as free eggs, milk and school lunches, are of particular benefit to those in the left-behind bracket. Programs to improve the lives of this special group have also been introduced, and funds earmarked for free health checks. A total of 2,000 boarding schools have been newly built or renovated in rural areas, and the dining rooms of 1,000 rural boarding schools refurbished.

The Chongqing municipal government has spent more than RMB 14.1 billion (US $2.25 billion) on bringing these measures into effect over the past two years, according to Zhou Xu, director of the Education Commission of Chongqing.

Efforts by the Chongqing municipal government to give more help to left-behind children were confirmed at the Meeting on Work for Rural Left-behind Children held at the end of 2011. Zhao Donghua, member of the Secretariat of the All-China Womens Federation, said at the meeting that the measures adopted in Chongqing are both practicable and effective and should be promoted in other regions around the country.

Similar programs have indeed come into effect in other parts of China. More than 3,700 institutions to guide and help left-behind children have been established, and 4,000 campaigns launched to recruit and train substitute parents for these children.

No substitute for parental responsibility

All the help, care and compassion that government and civil society give to left-behind children, however, could never compensate for the love and care of their real parents. This is the considered opinion of staff at the Education, Science, Culture and Public Health Committee of Chongqing Municipal Peoples Congress, the local legislature.

The committees research has shown that the parents of about 30 percent of left-behind children in Chongqing have not returned to their homes for three to five years. Also that 40 percent or more of left-behind children in poverty-stricken areas have had no contact with their parents for a year, and that some parents have neither been home nor had any contact with their children for as long as eight years.

Zhou Xu regards such a situation as a source of emotional pain for both children and parents. “During the Chongqing Municipal Peoples Congress survey, some children wept when asked about their parents. Others had nothing to say, but would cry while talking to their parents via phone or the Internet, and others still expressed resentment that their parents had left them,”Zhou said. He calls on both parents and the public to pay due attention to these childrens emotional state.

“Absence of parental love is the main problem of left-behind children, simply because their parents are never around,” said Su Fengjie, vice director of the National Working Committee on Children and Women under the State Council (NWCCW). “We should therefore emphasize the obligation and responsibility of parents as guardians and instill in them through training a stronger sense of responsibility.” Su pointed out that many parents are aware of the detrimental effect their absence has on their relationship with their kids, but nonetheless place greater importance on childrens studies and physical health. They consequently ignore symptoms of poor mental health often apparent in their children, such as being withdrawn and displaying antisocial tendencies.

Zhou Xu says the Chongqing municipal government plans to hold 9,000 lectures for rural parents in the municipality by 2015, thus ensuring attendance of 90 percent or more of rural families.

Su Fengjie believes that encouraging parents to return to their hometowns is the ultimate solution to the left-behind children phenomenon. Developing the local economy will induce laborers who left their homes in search of better jobs to come back, so greatly reducing numbers of children left to fend t are now gqing and g migrant ings rural m the 1.3

From migrant worker to urban resident

Yang Dongping, president of the 21st Century Education Development Research Institute, holds that urban acceptance of migrant workers is crucial to solving the problem of left-behind children. He advocates establishment of a public management system that allows migrant parents to bring their children to live with them in cities.

Ms. Zheng comes from Anhui Province, one of Chinas largest labor-exporting provinces. She has a job as nanny in Beijing, and her husband works on a construction site. “When I saw the child I take care of each day, I would miss my own kid far away in my hometown,” Zheng said. The desire to be with her son was so acute that she stopped living with her employers, rented a half basement and brought her son to Beijing. Zheng can now look forward to seeing her son, who is studying in a nearby elementary school for children of migrant workers, in their apartment each day after she finishes work. This makes her feel she finally has a real home in the city.

Not long ago, however, the local government shut down certain unlicensed migrant schools. This worries Zheng. As she said, “If my son cant go to school in Beijing, he will have to go back to our village in Anhui.” Although her son has free compulsory education back in their hometown, Zheng wants him near her. Being with his mom is also her sons biggest wish.

The Tongxin Experimental School in Chaoyang District in eastern Beijing is a school for children of migrant workers. Headmaster Wang Dezhi told China Today that most unlicensed schools for such children in Beijings northern Haidian District have been closed down. Some students have been transferred to licensed schools, but by no means all due to their limited capacity. Migrant schools like Tongxin are private and hence not entitled to government subsidies for the nineyear free education program. They normally charge tuition fees ranging from RMB 600 to 1,000 per semester. Parents are willing to pay the fees because they want their children to live with them rather than alone back in their rural hometowns. “A few years ago it was commonplace for about one third of our total students to transfer to other schools as their parents changed work locations or went back to their hometowns,” Wang Dezhi said. “Most of them now stay put, as more parents are finding work nearer their childrens schools.”

The Program for the Development of Chinese Children(2011-2020) promulgated in 2011 proposed efforts to promote reform of the residence permit (hukou) and social security systems, and to gradually ensure equal access for children of migrant workers in cities to compulsory education.

This concept has been acted upon in certain cities. In Shanghai, governments at both municipal and district level provide funds for migrant workers childrens free compulsory education. Consequently, since autumn of 2010, 470,000-odd mi- grant children have been able to enjoy free education at public and designated private schools. Among them, around 330,000, representing 71 percent of the total, are at public schools.

Since 2008, Shanghai has earmarked special funds, starting at RMB 2,000 per person per year, for migrant workers children to attend public schools. This subsidy, which is equally shared by municipal and district budgets, has since risen, yearon-year, to RMB 3,000, RMB 3,600 and RMB 4,000. In Hangzhou of neighboring Zhejiang Province, the local government stipulates that as long as migrant workers have residential permits, their children are entitled to the same rights in the province as locals to pre-school education and the nine-year compulsory education program. Many other cities have also begun taking action to resolve the problems of migrant childrens schooling and health care.

Certain schools that had been shut down have been reinstated to meet the huge demand, according to Wang Dezhi, who has been working in Beijing for 17 years. Wangs wife and three-year-old son now live with him in the capital. Wang calls on permanent urban residents to accept the many people like him who have been working and living in the city with their families for extended periods and who are unlikely to go back to their rural homes. Migrant workers children in Beijing now also receive free vaccines. Wang is confident that in the near future they will also be eligible for free education.

Once cities are ready to accept migrant workers and their children as permanent residents, the number of left-behind children in rural areas will rapidly decline.