The Hidden Risks in China’s Leapfrog Overseas Acquisitions

LIU QIONG

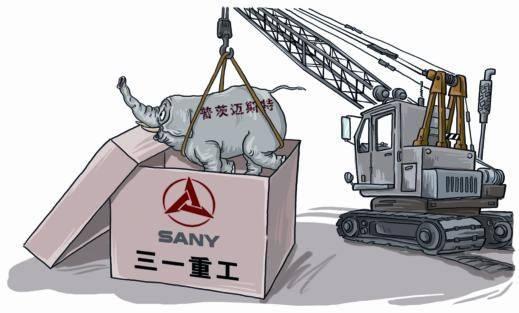

IT reads like a love story. “After 18 years of unrequited love, were finally together, having formed a union in only half a month of courtship,” said Xiang Wenbo.

But Xiang is no Romeo. Hes a businessman, and he made the above quote in his capacity as president of Chinas SANY Heavy Industry. Xiang waxed lyrical with regards to the groups successful acquisition of Germany-based Putzmeister, a leading global concrete machinery manufacturer, last April. “You could say Ive been longing for her [Putzmeister] for 18 years,” he said.

Hot on the heels of SANYs global wheeling and dealing, in May 2012, Dalian Wanda Group officially announced its purchase of AMC Entertainment Inc., the worlds second largest movie theater chain, for US $2.6 billion. Wanda also indicated that it would immediately invest at least US $500 million to sure up the chains operations.

As a matter of fact, in the first half of this year, large global acquisitions were not rare for Chinese companies operating overseas. Data from the Ministry of Commerce indicated the volume of Chinas non-financial overseas direct investment reached US $35.4 billion in the first half of the year, representing a year-on-year increase of 48.2 percent. Transnational acquisitions accounted for one third of the total investment volume.

Despite the buoyancy of Chinese enterprises global acquisitions, navigating the global economy remains a tricky task for Chinese enterprises overseas. The challenge has been particularly pronounced since the global financial crisis.

Another issue facing the countrys leading businesses abroad is a lack of experience in international corporate management. A recent survey indicated that the failure rate of Chinese corporations overseas investment is around 67 percent, while the international average stands at roughly 50 percent.

Bucking the Globalization Trend

Zhou Shuyuan is general manager of Towers Watson Mergers & Acquisitions(China), a U.S.-based global professional services firm. She points out that Chinese firms have eschewed the conventional “Uppsala” model of globalization, whereby firms enter foreign countries in increasing order according to the “cultural distance” from the home country and gradually increase their commitment to a particular country once they learn about it. Rather, most Chinese corporations have adopted a “leapfrog strategy”in their globalization processes.

A 2012 study of Chinese transnational enterprises released by Towers Watson indicated that 57 percent of surveyed Chinese firms had first entered the more expansive markets of North America, Europe, Middle East and Africa before they entered neighboring Asian emerging markets. Africa and the Middle East have been the main beneficiaries of Chinese investment.

Prior to the sensational global acquisitions made by Wanda and SANY Heavy Industry, a dozen Chinese firms had already been operating under the leapfrog model. These include automobile manufacturer Geely Holding Group in its acquisition of the Volvo Group, furniture manufacturer Mengnu Group in its merger with U.S.-based sofa bed seller Jennifer Convertibles, and Ausnutria Dairy Corporation with its acquisition of Netherlands-based Hyproca Dairy Group.

So why are so many Chinese transnational enterprises adhering to the leapfrog model in their global expansion?

Liu Wenbo, vice president and partner of Roland Berger Strategy Consultants Greater China, indicated that Chinese companies, by directly entering the relatively high-end European and American markets instead of exploring the developing markets more similar to Chinas, could improve their abilities in management, technology and product development in a short time frame through mergers and acquisitions. “In particular, after the global financial crisis and the European debt crisis, and as asset values in Europe and North America plummeted, the tendency for Chinese firms to employ the leapfrog model has become increasingly apparent,” Liu added.

In some cases, however, Chinese firms have been compelled to adopt the “leap- frog model” owing to circumstances, Zhou pointed out. In terms of the distribution of global mineral resources, for example, most high quality, readily accessible mineral resources have been held by global energy giants like BP and BHP Billiton. Chinese firms, in their efforts to secure their own sources of mineral wealth, have had to head for marginal or politically turbulent regions in the Middle East and Africa.

Of course, some enterprises have chosen the leapfrog model according to their corporate management principles. For example, to improve product quality and service levels, Haier Group has been following the principle of “difficult first, easy later.” Accordingly, it first entered developed countries and then expanded to neighboring countries. In 1990 Haier exported 20,000 refrigerators to Germany, its first sales in the international market. Now Haier is number one in Germanys market for multi-door refrigerators, with a market share of 75.9 percent.

Buffering Against Leapfrog Risks

In contrast to the traditional Uppsala model, which champions low exposure to risk and a prolonged globalization process, the leapfrog strategy could spell huge operational risks for firms. On the plus side, “leapfrogging” firms can become truly global in a short space of time.

In Zhou Shuyuans opinion, although Haiers unconventional expansion strategy has seen great success, its model is not suitable for many Chinese enterprises. By exposing themselves to high product development, marketing and production costs, Chinese firms following Haiers example put themselves at considerable financial risk.

In carrying out cross-national business operations, most firms from developed countries have decades or over a century of management expertise and experiences to fall back on, Zhou elaborated. However, as Chinese enterprises rapidly expand their business abroad, many are equipped with only a short history in global business management, or with none at all. Even the most experienced Chinese firms can only boast 20 to 30 years of international operations.

In addition, some overseas Chinese enterprises are crippled by their domestic management mindset. With little understanding of foreign business cultures, some have suffered public relation crises abroad. Such issues hamper their ability to successfully do business overseas.

Many Chinese enterprises are further handicapped by their lack of international management talent and negotiation prowess. By failing to introduce international talent into their businesses, some Chinese companies that make global acquisitions have been unable to achieve genuine and effective global resource integration.

Differences in the legal systems of China and other countries can also lead to troubles in global expansion. For example, great differences exist between the Chinese and French legal systems concerning the rights of sacked employees. Due to its ignorance of French laws, after acquiring Thomson SA, a French technology and media services company, Chinas TCL Group found itself having to pay 270 million Euros in compensation for laid-off employees.

In an international management forum held at Fudan University, Xiang commented that it is inclusion, rather than transformation, that should be emphasized once global acquisitions have been made. “If I married a German woman, I think its impossible for me to remodel her into a Chinese lady, and vice versa. Accordingly, after it merged with Putzmeister in Germany, SANY didnt assign one Chinese employee to Putzmeister. Still the companys profits have increased markedly in the months after the acquisition. I think that to make successful global acquisitions, firms need to truly adapt to the local environment by taking full advantage of local employees.”

Bargain Hunting and Its Pitfalls

When discussing Chinese companiesforeign investments against the backdrop of the global financial crisis and the Eu- ropean debt crisis, many domestic commentators like to use the term chaodi, meaning “to buy something at the lowest price.”

Xue Qiuzhi, vice dean of the School of Management at Fudan University, said there were two different ways to chaodi.

The first way usually involves firms conducting a long-term study of overseas markets and enterprises, and making their acquisitions when prices hit cyclical lows. This kind of chaodi, Xue says, is a reasonable form of investment.

However, enterprises should be wary of another kind of chaodi, he says. Commissioned by their clients, its quite common for investment institutions to hoodwink Chinese firms into purchasing non-performing assets abroad. For this, investment institutions walk away with sizable commission fees, and Chinese firms are left with clunkers.

But more generally, gung-ho Chinese enterprises, lured by low asset prices, can become trapped in their overseas investments without a long-term business plan and lacking the local talent to successfully integrate with overseas assets and resources.

Problems in global management have been recognized as some of the major challenges for enterprises in their overseas expansion and acquisitions. “Chinese enterprises are usually weak in their ability to integrate international assets and resources, as well as in their crossculture management. How to successfully integrate with purchased enterprises and achieve their management goals is a big problem,” Xue noted.

In their global operations, many Chinese transnational corporations also face a host of other conundrums: How do we achieve unified management domestically and abroad? How do we balance power and responsibilities between our headquarters and overseas subsidiaries? How do we achieve effective control and cost-effective management of subsidiaries while bringing their flexibility and advantages into full play?

“Whats encouraging is that Chinabased transnational companies have realized their weaknesses, and are endeavoring to improve their management systems,” Zhou Shuyuan remarked. One thing is for sure: expanding overseas has been – and continues to be – a steep learning curve for ambitious Chinese firms.