Autoimmune pancreatitis versus pancreatic cancer: a comprehensive review with emphasis on differential diagnosis

Kyriakos Psarras, Minas E Baltatzis, Efstathios T Pavlidis, Miltiadis A Lalountas, Theodoros E Pavlidis and Athanasios K Sakantamis

Thessaloniki, Greece

Autoimmune pancreatitis versus pancreatic cancer: a comprehensive review with emphasis on differential diagnosis

Kyriakos Psarras, Minas E Baltatzis, Efstathios T Pavlidis, Miltiadis A Lalountas, Theodoros E Pavlidis and Athanasios K Sakantamis

Thessaloniki, Greece

BACKGROUND:Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a rare form of chronic pancreatitis with a discrete pathophysiology, occasional diagnostic radiological findings, and characteristic histological features. Its etiology and pathogenesis are still under investigation, especially during the last decade. Another aspect of interest is the attempt to establish specific criteria for the differential diagnosis between autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, entities that are frequently indistinguishable.

DATA SOURCES:An extensive search of the PubMed database was performed with emphasis on articles about the differential diagnosis between autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer up to the present.

RESULTS:The most interesting outcome of recent research is the theory that autoimmune pancreatitis and its various extra-pancreatic manifestations represent a systemic fibroinflammatory process called IgG4-related systemic disease. The diagnostic criteria proposed by the Japanese Pancreatic Society, the more expanded HISORt criteria, the new definitions of histological types, and the new guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology help to establish the diagnosis of the disease types.

CONCLUSION:The valuable help of the proposed criteria for the differential diagnosis between autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer may lead to avoidance of pointless surgical treatments and increased patient morbidity.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 465-473)

autoimmune pancreatitis; pancreatic cancer; IgG4-related systemic disease; HISORt criteria

Introduction

Sarles et al[1]in 1961 were the first to use the term "autoimmune" in an attempt to clarify the etiology of "chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas". Since then, the disease has been referred to as sclerosing pancreatitis, primary inflammatory pancreatitis, nonalcoholic duct-destructive chronic pancreatitis, lymphoplasmatocytic sclerosing pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis with diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct, sclerosing pancreatocholangitis, and inflammatory pseudotumor. The term "autoimmune pancreatitis" (AIP) was eventually proposed by Yoshida et al[2]in 1995, who reported a case of chronic pancreatitis with hyperglobulinemia and serum autoantibodies responding to corticosteroid therapy. Current opinions agree that AIP is the pancreatic manifestation of a systemic autoimmune disease, affecting many other organs and causing lesions with common histological features and almost similar microscopic architecture. AIP is more common in males and the usual age of presentation is the 6th decade of life, although sporadic cases have been described even from the age of 20.[2]Recently, two types of AIP have been distinguished, type 1 or lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis (LPSP) and type 2 or idiopathic duct centric pancreatitis (IDCP) or granulocyte epithelial lesion (GEL). Clinically, these two typies have comparable presentations but differ significantly in their demography, serological characteristics, other organ involvement, and relapse rate.[3]

Pathogenesis

Autoimmunity is probably implicated in the pathogenesis of AIP as indicated mainly by specific serologic abnormalities (presence of autoantibodies and elevated levels of γ-globulin) and secondarily by the dramatic response observed after steroid therapy. Antibodies against lactoferrin and carbonic anhydrase-II and IV are the most frequently detected autoantibodies in AIP (73% and 54% respectively).[4]Antibodies against pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) are additionally detected in 30%-40% of cases.[5]Patients may also have autoantibodies against rheumatoid factor, smooth muscle antigens, and nuclear antigens. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyteassociated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), which is expressed on activated T-cells, regulates T-cell stimulation and singlenucleotide polymorphisms identified in CTLA-4 are associated with susceptibility to autoimmune diseases.[6]Moreover, Fc receptor-like 3 (FCRL3) polymorphisms (expressed on B-cells) have also been shown to contribute to autoimmune mechanisms.[7,8]

In 2005, Guarneri et al[9]claimed the possible involvement of Helicobacter pylori in the stimulation of the autoimmune process in AIP as indicated by the significant homology found between human carbonic anhydrase-II and α-carbonic anhydrase of H. pylori. According to this hypothesis, patients with H. pylori infection are susceptible to developing AIP via molecular mimicry. Frulloni et al[10]discovered that 94% of patients with AIP have antibodies against the plasminogen-binding protein of H. pylori, which reinforces this hypothesis. A synopsis of all antibodies involved in AIP pathogenesis is presented in Table 1.

Elevated levels of γ-globulin in the serum is a characteristic finding in type 1 AIP. The majority of these antibodies belong to the IgG4 subclass, which normally accounts for 3%-6% of total serum IgG but is significantly increased in AIP.

Clinical presentation

AIP usually manifests either as acute or chronic symptomatic pancreatitis. However, in many cases the predominant symptoms derive from extra-pancreatic disease. The acute syndrome may appear with jaundice (40%-80%), diabetes mellitus (40%-70%), mild abdominal pain (35%), weight loss (33%) and, less frequently, with a persistent pancreatic mass. Diabetes mellitus may be the only presenting symptom. In the postacute phase, pancreatic atrophy and exocrine dysfunction may cause steatorrhea. Gradually aggravated pancreatic insufficiency is the inevitable outcome. The involvementof other organs (bile ducts, salivary glands, kidneys, retroperitoneum) causes extra-pancreatic symptoms, which occasionally appear to be the predominant or even the sole manifestation of the disease.

Table 1. Antibodies involved in AIP pathogenesis

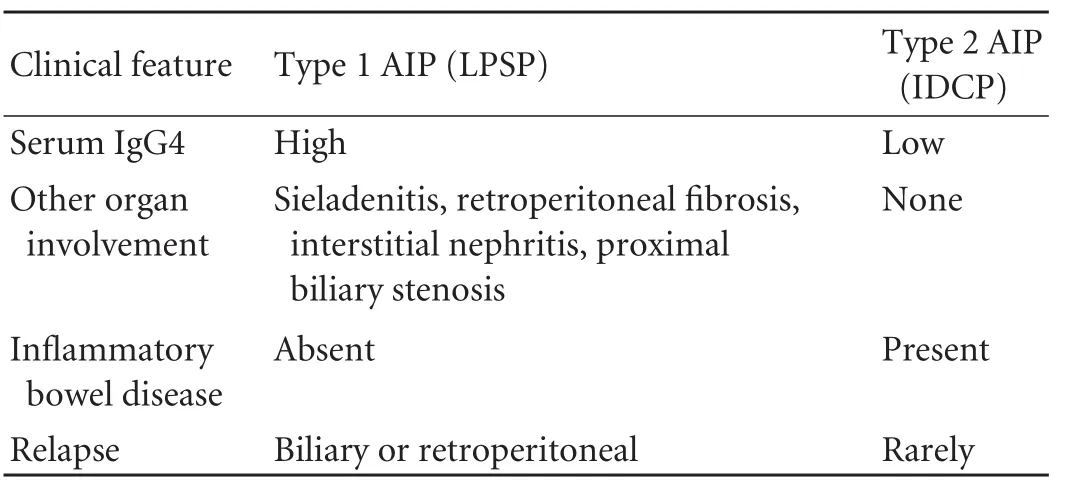

Table 2. Clinical profiles of type 1 AIP (LPSP) and type 2 AIP (IDCP)

The two AIP types have distinctive clinical features, which are summarized in Table 2. Type 1 AIP (LPSP), presents predominantly with obstructive jaundice in the elderly and responds to steroid therapy. Type 2 AIP (IDCP) seems not to be a systemic disease but a pancreas-specific disorder. It is not associated with either serum IgG4 elevation or with other organ involvement.[3]

The presence of extra-pancreatic symptoms, in combination with specific imaging and laboratory findings, contributes to the differential diagnosis between diffuse pancreatic enlargement in AIP and edematous acute pancreatitis.

Jaundice, weight loss, abdominal pain and an abrupt onset of diabetes mellitus in the elderly are symptoms presenting in pancreatic cancer as well. Exocrine insufficiency is less common in pancreatic cancer than in AIP, while the presence of marked anorexia, cachexia and narcotic-requiring pain rather establishes the diagnosis of cancer. Nevertheless, for the majority of patients the differential diagnosis between AIP and pancreatic cancer based on clinical manifestations alone is regarded as a very ambitious intention.

Laboratory tests

As mentioned previously, a representative finding in patients with AIP is the high serum levels of γ-globulins. Hamano et al[11]first reported in 2001 the correlation between high serum concentration of IgG4 antibodies and AIP, which was not observed in patients with other forms of chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis and Sjögren syndrome. IgG4 serum levels >135 mg/dL reflected high rates of sensitivity and specificity for AIP diagnosis (95% and 97%, respectively). Hirano et al[12]in 2005 obtained comparable results. However, more recently, Ghazale et al[13]have regarded high serum IgG4 concentration as an indication but not diagnostic for AIP. As for the extra-pancreatic lesions of AIP, Kamisawa et al[14]in 2008 reported that in AIP patients with serum IgG4 levels ≥220 mg/dL, involvement of other organs was frequent. It is essential to mention at this point that approximately only 1% of all patients with pancreatic cancer have a serum IgG4 level greater than 2-fold the upper limit of normality (50 mg/dL). Mild (<2-fold) elevations of serum IgG4 are seen in up to 10% of subjects without AIP and cannot be used alone for differential diagnosis.[14]It is interesting that while LPSP is associated with elevated titers of autoantibodies, IDCP does not have definitive serological autoimmune biomarkers. This is the reason for debates and concerns regarding use of the term "autoimmune" to describe IDCP.[3]

The levels of serum amylase and lipase are mildly elevated in AIP (approximately 3-fold). The levels of cholestatic enzymes, transaminases and bilirubin are frequently elevated when cholestasis is present because of edema of the head of the pancreas or extra-pancreatic disease with common bile duct involvement.[15]CA19-9 levels higher than 200 U/mL are rare in AIP, while patients with pancreatic cancer may have significantly higher CA19-9 levels.[16]

Imaging studies

Fig. 1. Diffuse type of autoimmune pancreatitis with sausageshaped pancreatic enlargement and a hypodense (capsule-like) rim around the body and tail of the pancreas.

Fig. 2. Focal type of autoimmune pancreatitis in the head of the pancreas, resembling pancreatic cancer. Definite diagnosis was made after biopsy.

Computed tomography (CT) may occasionally produce characteristic images of the disease. Two morphological types of AIP are encountered in CT images: typical "diffuse type" and more rare "focal type". The first is characterized by a diffusely enlarged sausage-shaped pancreas and a diffusely irregular and attenuated pancreatic duct. Moreover, a hypodense (capsulelike) rim is visible around the pancreas and is probably due to inflammatory and fibrotic changes in the peripancreatic fat (Fig. 1). The focal type of AIP consists of a focal pancreatic mass accompanied by a segmental pancreatic duct stricture and can be hardly distinguished from pancreatic cancer[16](Fig. 2). The lesion appears hypodense on early phase imaging and isodense in the delayed phase, which is a common appearance of cancer as well.[17]The presence of peripancreatic lymphadenopathy, frequent in either AIP or cancer, is another finding that could lead to an erroneous diagnosis.[18]However, distant metastases or infiltration of adjacent tissues is highly indicative of cancer, which is also suggested by post-obstructive dilation of the pancreatic duct. On the other hand, non-metastatic involvement of other organs enhances the suspicion of AIP.[16]For the time being, conventional MRI and PET scan have not been proved to be more efficient than CT either for the diagnosis of AIP or for cancer exclusion.[16]Magnetic resonance elastography, a new technique, which detects wave propagation velocity through the human body, can determine tissue elasticity or stiffness and therefore contribute to the evaluation of pancreatic lesions and exclusion of malignancy.[19]

Fig. 3. ERCP showing diffuse irregular stenosis of the pancreatic duct caused by autoimmune pancreatitis.

On endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct is rather specific to AIP and is rarely encountered in pancreatic cancer[20](Fig. 3). However, differential diagnosis is difficult in patients with segmental narrowing of the duct. In a recent study, the narrowed portion of the main pancreatic duct was found to be significantly longer in AIP (6.7±3.2 cm) than in cancer cases (2.6±0.8 cm).[21]Furthermore, in AIP patients with segmental narrowing, post-stenotic dilatation of the distal duct is a rare finding (diameter 2.9± 0.7 mm), whereas it is frequent in cancer (diameter 7.1± 1.9 mm).[21]Side branches from the narrowed portion are more often visible in AIP than in cancer. Complete obstruction is mainly observed in malignant lesions. On ERCP, stenosis of the lower bile duct may be detected in patients with either AIP or cancer. Brushing cytology of the narrowed portion of the duct plays a significant role in the differential diagnosis. The presence of strictures in the extra-pancreatic portion of the common bile duct or in the hepatic ducts and their branches obviously cannot be associated with cancer, making the diagnosis of AIP more likely. Biopsies taken from a swollen major duodenal papilla (presented in 25% of AIP cases) show dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis. Abundant infiltration of the swollen papilla with IgG4-positive plasma cells is specifically detected in AIP cases.[22,23]

Secretin-enhanced MRCP is a method of great diagnostic importance, especially in those cases where ERCP proves unsuccessful. Intravenous administration of secretin increases bile and pancreatic juice secretion and therefore improves the ductal imaging producing better images. The so-called "duct-penetrating sign" which corresponds to a stenotic change of the main pancreatic duct without definite ductal wall irregularity is a highly suggestive sign of AIP.[24,25]

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) in patients with AIP shows either a diffuse hypoechoic enlargement of the pancreas or a focal irregular hypoechoic mass with or without peripancreatic lymphadenopathy. In the second case the differential diagnosis from cancer is facilitated by the presence of hyperechoic spots within the mass, which may represent compressed pancreatic ducts.[26]Conventional abdominal ultrasonography findings are essentially similar to those of EUS, which, however, is preferable due to its higher resolution and clearer images of the pancreatic parenchyma. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is very helpful for excluding the possibility of pancreatic cancer,[27]although the small samples make this method insufficient for the diagnosis of AIP. Endoscopic EUS-guided Tru-Cut biopsy provides sufficient tissue and architecture preservation to permit histological diagnosis with low complication rates in experienced hands.[28]

EUS-elastography and contrast-enhanced EUS technology have many advantages over conventional EUS. A homogenous stiffness pattern of the lesion in EUS-elastography characterizes the majority of AIP cases.[29]In contrast-enhanced EUS, AIP lesions appear to be homogeneously hypervascular, whereas pancreatic cancer is mainly hypovascular, compared with normal pancreas.[30]

Histology

LPSP or AIP without GELs shows 4 characteristic histopathological features: 1) dense infiltration of plasma cells and lymphocytes, particularly periductal; 2) peculiar storiform fibrosis; 3) venulitis with lymphocytes and plasma cells often leading to obliteration of the affected veins; and 4) abundant (>10 cells per high-power field [HPF]) immunoglobulin-IgG4 positive plasma cells.[31]IDCP is characterized by GELs, not seen in LPSP. Intraluminal and intraepithelial neutrophils are present in medium-sized and small ducts as well as in acini, frequently leading to the obliteration and destruction of the lumen. The amount of IgG4-positive plasma cells varies but usually is low (<10 cells/HPF or none).[31]

It is unclear whether these subgroups are different stages of the autoimmune process in AIP or represent different diseases. Sah et al[32]in 2010 attempted to accentuate the differences between the two histological subgroups based on 97 patients with AIP. According to this study, patients with LPSP are older than those with IDCP (mean age 62 vs 48 years) have higher serum IgG4 concentrations and are more prone to extrapancreatic manifestations. However, there was no significant difference between the two types regarding the 5-year survival.

The distinction of AIP in two discrete histopathological types was included in the conclusionsof the "Honolulu consensus", although there was a vigorous debate about the autoimmune etiology of IDCP, mostly because of the lack of a convincing theory for the granulocyte infiltration and the autoimmune mechanism involved.[3]

Treatment

Steroids are regarded as the cornerstone of treatment for AIP, although a few sporadic cases treated with spontaneous resolution have been reported.[33,34]Prednisone (40 mg daily for 4 weeks, gradually tapered for the next 8 weeks) is the most commonly used regimen. The need for maintaining a low-dose after resolution has been documented either preventively or after relapse. Azatheioprine and other immunosuppressive drugs have been tested with encouraging results, but the present data are not sufficient for their use in daily practice. Steroid therapy also has a positive effect in some of the secondary manifestations of the disease, like diabetes mellitus, and in most of the extra-pancreatic lesions. However, it is unclear if it is similarly effective regarding the exocrine function. There is some controversy about the usage of steroids for diagnostic purposes, based on the idea that a response to therapy establishes the diagnosis of AIP. Diagnostic steroid trials should be conducted carefully by pancreatologists only after a negative work-up for cancer including EUS-FNA. It is also worth mentioning that there is a high recurrence rate in type-1 AIP patients after steroid therapy, whereas in type-2 AIP patients relapse is infrequent.[31]

Extra-pancreatic manifestations

Type 1 AIP may affect other organs and tissues (30%-50% of patients) in contrast to type 2, where this is not common. These tissues show similar histological changes, including increased IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration and response to corticosteroid therapy.

The biliary tract is the most commonly (>70%) involved extra-pancreatic site in patients with AIP[35]and the term "IgG4-associated cholangitis" has replaced the previous term "sclerosing cholangitis".[36]Radiographically, IgG4-associated cholangitis is characterized by bile duct wall thickening and biliary strictures. Serum IgG4 is usually elevated (a sensitivity of 74%) and the histological architecture of the lesions is similar to that seen in the pancreas. On ERCP, stenosis of the lower common bile duct may be detected in both AIP and pancreatic cancer, whereas extra-pancreatic stenosis or stenosis of the intrahepatic ducts is indicative of AIP with coexistent IgG4-associated cholangitis. Clinical and radiological findings of IAC may mimic those of primary sclerosing cholangitis. However, the diffuse distribution of primary sclerosing cholangitis with a more frequent involvement of the smaller intrahepatic bile ducts, the "beaded" and "pruned-tree" figure, p-ANCA elevation and the absence of pancreatic disease facilitate the differential diagnosis.[37]Stenosis of the hilar bile duct should also be distinguished from cholangiocarcinoma of the hepatic hilus. The absence of pancreatic lesions and their resolution with steroid therapy are the clues for diagnosis.[38]

Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the liver in AIP has been reported in several studies, inducing several patterns: portal inflammation with or without interface hepatitis, large bile duct obstruction, portal sclerosis, lobular hepatitis and canalicular cholestasis,[39]which may coexist in the same patient and are described by the term IgG4-hepatopathy. The lymphoplasmacytic type of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor in the hepatic hilum is regarded as another aspect of liver involvement in AIP patients.[40]

The gallbladder is frequently affected in AIP. Diffuse, acalculus, lymphoplasmacytic cholecystitis appears with deep mural and extramural inflammation and is characterized by the same serum and histological findings as in AIP.[41]

The salivary and lacrimal glands may also be affected. Kuttner tumor, a chronic sclerosing sieladenitis presenting with asymmetric firm swelling of the submandibular glands, shows marked lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis and destruction of the glandular lobules. These common immunohistochemical characteristics with AIP also reinforce the suggested correlation.[42]Miculicz disease, an idiopathic, bilateral, painless and asymmetric swelling of the lacrimal, parotid and submandibular glands, was previously considered to be a subtype of Sjögren syndrome. However, the histological similarity with AIP, the elevated serum concentration of IgG4 (which is low in Sjögren syndrome) and the absence of anti-SSA or anti-SSB autoantibodies has led to reconsideration of the etiology of this disease.[43,44]

Several cases of retroperitoneal fibrosis associated with AIP have been reported, characterized by lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (lymphoid follicles with germinal centers).[45,46]IgG4-related periarteritis of the retroperitoneal arteries may coexist with retroperitoneal fibrosis.[47]Akram et al[48]reported that 33% of 92 patients with sclerosing mesenteritis had abundant IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltrates in the small bowel mesentery. It seems likely that IgG4-relatedimmunopathologic processes might be involved in the pathogenesis of some cases of sclerosing mesenteritis.

Other organs with lesions possibly associated with AIP are the kidney (tubulointerstitial lymphoplasmacytic nephritis),[49]breast (inflammatory pseudotumor),[50]lung (interstitial pneumonia or inflammatory pseudotumor),[51]lymph nodes (Castleman disease-like features, follicular hyperplasia),[52,53]thyroid (Riedel thyroiditis)[54]and prostate (IgG4-related prostatitis).[55]

All the extrapancreatic lesions noted above typically have pathologic features similar to those of type 1 AIP, increased serum level of IgG4 is a common finding, partial or complete resolution following steroid therapy, and may be present despite the absence of pancreatic disease. Thus, a new clinicopathologic concept, called IgG4-related systemic disease has been proposed as a unique autoimmune inflammatory condition in order to include all these lesions.[56]

As noted above, type 2 AIP is not usually associated with other organ involvement. However, in 30% of reported cases of IDCP inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis) it is present as well.[3,31]

Diagnostic criteria

The most significant diagnostic consideration in a patient presenting with obstructive jaundice and a pancreatic mass is pancreatic cancer. AIP may present with the same manifestations and could be an alternative diagnostic. However, usually the diagnosis is not made before surgical treatment is undertaken. Nakazawa et al[57]reported that in 20% of AIP cases the diagnosis is made after surgery.

Attempting to establish applicable diagnostic guidelines, the Japan Pancreas Society proposed specific criteria for AIP in 2002.[58]Great emphasis was given to the presence of typical imaging findings: diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, diffuse main pancreatic duct narrowing (>1/3 of the length) with an irregular wall (mandatory criteria). Elevated serum autoantibodies, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and pancreatic fibrosis were characterized as supportive criteria. According to the Japan Pancreas Society, the diagnosis of AIP is established if the mandatory criteria together with at least one of the supportive criteria are present. The more recent Korean criteria[59]and the modified Japanese criteria (2006)[60]also focus mainly on the imaging characteristics of AIP, which are not always helpful, especially in cases of focal disease. The presence of extra-pancreatic lesions was not included in these criteria; this is considered to be another major disadvantage.

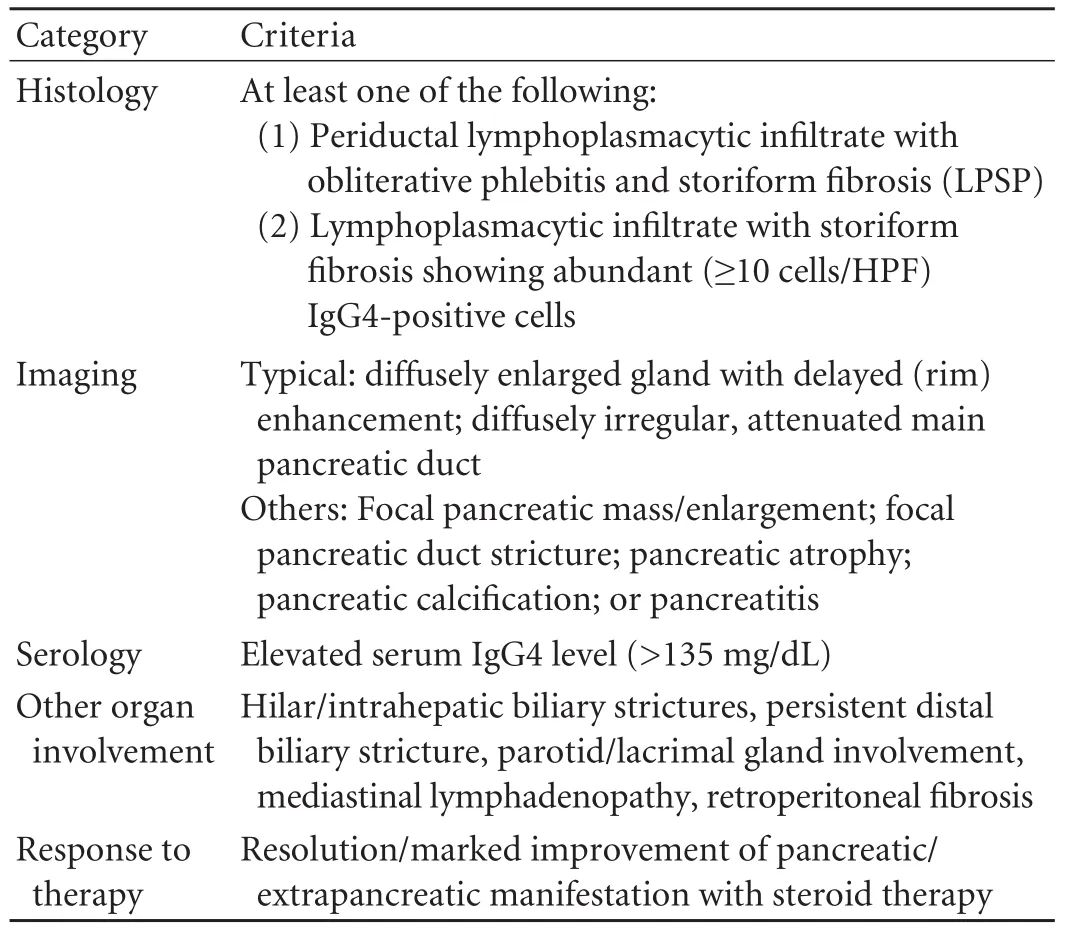

In 2007, Chari et al[61,62]proposed expanded diagnosticfeatures, called the "HISORt criteria". According to these, there are five cardinal features of AIP: histology, imaging, serology, other organ involvement and response to therapy (Table 3). Three diagnostic groups are proposed by the combined HISORt criteria. Group A includes only histological findings which are adequate to establish the diagnosis. Group B requires the presence of characteristic imaging features plus abnormal serology. Finally, Group C includes patients with unexplained pancreatic disease accompanied by abnormal serology, other organ involvement and response to steroid therapy. The HISORt criteria use a wider spectrum of AIP manifestations than the Japanese criteria, reflecting the current understanding of the disease as a systemic steroid-responsive disorder.

Table 3. The HISORt criteria for AIP diagnosis

More recently, following recent knowledge, Chari et al[3]at the Honolulu consensus reconsidered the above criteria and distinguished the two histological types of AIP. Furthermore, Shimosegawa et al[31]announced the guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology, which included the so far proposed criteria customized into the two discrete subtypes of AIP and further categorized as level 1 or level 2 according to their diagnostic reliability. Specific diagnostic algorithms were proposed based on this new classification. Some key points worth mentioning are: a) type 1 and type 2 AIP seem to be indistinguishable if only imaging and response to steroids are taken into account; b) high levels of IgG4 and other organ involvement are indicative for the diagnosis of type 1 AIP; c) inflammatory boweldisease is associated mostly with type 2 AIP; a low IgG4 titer and the absence of extra-pancreatic lesions are indicative but not diagnostic for IDCP; d) histological confirmation is mandatory in type 2, while in type 1 the other criteria may be sufficient; and e) patients with atypical histology are now included in a new category called AIP-not otherwise specified.[31]

Table 4. Differential diagnosis between AIP and pancreatic cancer: important points

Based on the above criteria, the diagnosis of AIP can be achieved in most cases. However, especially in the case of focal AIP, the differential diagnosis from pancreatic cancer is not always easy. A summary of the key points for the differential diagnosis between AIP and pancreatic cancer are placed side by side in Table 4.

Conclusion

Since the term "autoimmune pancreatitis" was introduced in 1995, significant progress has been made regarding clinical, serologic, radiologic and pathologic evaluation of the disease. The new clinicopathologic entity of IgG4-related systemic disease seems to be a challenge for further research, which may lead to improved understanding of the pathogenesis, the autoimmune mechanisms involved and the development of new diagnostic biomarkers for the disease. Regarding the differential diagnosis from pancreatic cancer, the HISORt criteria and the recent guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology are a valuable aid for the clinician and could prevent pointless pancreatectomies. Diagnosis of AIP is important for the additional reason of its response to corticosteroid therapy, in contrast to other forms of chronic pancreatitis, where any treatment is mainly palliative.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:PK wrote the main body of the article with the help of BME and PET under the supervision of PTE. PET and LMA provided advice on literature data and their interpretation, while PTE and SAK provided advice on surgical aspects. SAK is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Sarles H, Sarles JC, Muratore R, Guien C. Chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas--an autonomous pancreatic disease? Am J Dig Dis 1961;6:688-698.

2 Yoshida K, Toki F, Takeuchi T, Watanabe S, Shiratori K, Hayashi N. Chronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune abnormality. Proposal of the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:1561-1568.

3 Chari ST, Kloeppel G, Zhang L, Notohara K, Lerch MM, Shimosegawa T. Histopathologic and clinical subtypes of autoimmune pancreatitis: the honolulu consensus document. Pancreas 2010;39:549-554.

4 Okazaki K, Uchida K, Ohana M, Nakase H, Uose S, Inai M, et al. Autoimmune-related pancreatitis is associated with autoantibodies and a Th1/Th2-type cellular immune response. Gastroenterology 2000;118:573-581.

5 Asada M, Nishio A, Uchida K, Kido M, Ueno S, Uza N, et al. Identification of a novel autoantibody against pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2006;33:20-26.

6 Scalapino KJ, Daikh DI. CTLA-4: a key regulatory point in the control of autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev 2008;223: 143-155.

7 Kochi Y, Yamada R, Suzuki A, Harley JB, Shirasawa S, Sawada T, et al. A functional variant in FCRL3, encoding Fc receptor-like 3, is associated with rheumatoid arthritis and several autoimmunities. Nat Genet 2005;37:478-485.

8 Umemura T, Ota M, Hamano H, Katsuyama Y, Kiyosawa K, Kawa S. Genetic association of Fc receptor-like 3 polymorphisms with autoimmune pancreatitis in Japanese patients. Genetic association of Fc receptor-like 3 polymorphisms with autoimmune pancreatitis in Japanese patients. Gut 2006;55:1367-1368.

9 Guarneri F, Guarneri C, Benvenga S. Helicobacter pylori and autoimmune pancreatitis: role of carbonic anhydrase via molecular mimicry? J Cell Mol Med 2005;9:741-744.

10 Frulloni L, Lunardi C, Simone R, Dolcino M, Scattolini C, Falconi M, et al. Identification of a novel antibody associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2135-2142.

11 Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A, Unno H, Furuya N, Akamatsu T, et al. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2001;344: 732-738.

12 Hirano K, Kawabe T, Yamamoto N, Nakai Y, Sasahira N, Tsujino T, et al. Serum IgG4 concentrations in pancreatic and biliary diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2006;367:181-184.

13 Ghazale A, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, et al. Value of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis and in distinguishing it from pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1646-1653.

14 Kamisawa T, Imai M, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A. Serum IgG4 levels and extrapancreatic lesions in autoimmune pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;20:1167-1170.

15 Lara LP, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2005;7:101-106.

16 Wakabayashi T, Kawaura Y, Satomura Y, Watanabe H, Motoo Y, Okai T, et al. Clinical and imaging features of autoimmune pancreatitis with focal pancreatic swelling or mass formation: comparison with so-called tumor-forming pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:2679-2687.

17 Irie H, Honda H, Baba S, Kuroiwa T, Yoshimitsu K, Tajima T, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: CT and MR characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;170:1323-1327.

18 Procacci C, Carbognin G, Biasiutti C, Frulloni L, Bicego E, Spoto E, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: possibilities of CT characterization. Pancreatology 2001;1:246-253.

19 Mariappan YK, Glaser KJ, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography: a review. Clin Anat 2010;23:497-511.

20 Kamisawa T, Anjiki H, Takuma K, Egawa N, Itoi T, Itokawa F. Endoscopic approach for diagnosing autoimmune pancreatitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010;2:20-24.

21 Kamisawa T, Imai M, Yui Chen P, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, et al. Strategy for differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 2008;37:e62-67.

22 Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Nakajima H, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A. Usefulness of biopsying the major duodenal papilla to diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis: a prospective study using IgG4-immunostaining. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:2031-2033.

23 Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A. A new diagnostic endoscopic tool for autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:358-361.

24 Carbognin G, Girardi V, Biasiutti C, Camera L, Manfredi R, Frulloni L, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: imaging findings on contrast-enhanced MR, MRCP and dynamic secretinenhanced MRCP. Radiol Med 2009;114:1214-1231.

25 Ichikawa T, Sou H, Araki T, Arbab AS, Yoshikawa T, Ishigame K, et al. Duct-penetrating sign at MRCP: usefulness for differentiating inflammatory pancreatic mass from pancreatic carcinomas. Radiology 2001;221:107-116.

26 Hyodo N, Hyodo T. Ultrasonographic evaluation in patients with autoimmune-related pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2003; 38:1155-1161.

27 Deshpande V, Mino-Kenudson M, Brugge WR, Pitman MB, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of autoimmune pancreatitis: diagnostic criteria and pitfalls. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1464-1471.

28 Levy MJ, Reddy RP, Wiersema MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Harewood GC, et al. EUS-guided trucut biopsy in establishing autoimmune pancreatitis as the cause of obstructive jaundice. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;61:467-472.

29 Buscarini E, Lisi SD, Arcidiacono PG, Petrone MC, Fuini A, Conigliaro R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography findings in autoimmune pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17: 2080-2085.

30 Hocke M, Ignee A, Dietrich CF. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Endoscopy 2011;43:163-165.

31 Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas 2011;40: 352-358.

32 Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R, Sugumar A, Clain JE, Levy MJ, et al. Differences in clinical profile and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:140-148.

33 Ito T, Nishimori I, Inoue N, Kawabe K, Gibo J, Arita Y, et al. Treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis: consensus onthe treatment for patients with autoimmune pancreatitis in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2007;42:50-58.

34 Ozden I, Dizdaroglu F, Poyanli A, Emre A. Spontaneous regression of a pancreatic head mass and biliary obstruction due to autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2005;5:300-303.

35 Nishino T, Toki F, Oyama H, Oi I, Kobayashi M, Takasaki K, et al. Biliary tract involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2005;30:76-82.

36 Bjornsson E, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Lindor K. Immunoglobulin G4 associated cholangitis: description of an emerging clinical entity based on review of the literature. Hepatology 2007;45: 1547-1554.

37 Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Sano H, Ando T, Aoki S, Kobayashi S, et al. Clinical differences between primary sclerosing cholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis with autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2005;30:20-25.

38 Hamano H, Kawa S, Uehara T, Ochi Y, Takayama M, Komatsu K, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing cholangitis that mimics infiltrating hilar cholangiocarcinoma: part of a spectrum of autoimmune pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:152-157.

39 Umemura T, Zen Y, Hamano H, Kawa S, Nakanuma Y, Kiyosawa K. Immunoglobin G4-hepatopathy: association of immunoglobin G4-bearing plasma cells in liver with autoimmune pancreatitis. Hepatology 2007;46:463-471.

40 Zen Y, Fujii T, Sato Y, Masuda S, Nakanuma Y. Pathological classification of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with respect to IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol 2007;20:884-894.

41 Wang WL, Farris AB, Lauwers GY, Deshpande V. Autoimmune pancreatitis-related cholecystitis: a morphologically and immunologically distinctive form of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing cholecystitis. Histopathology 2009;54:829-836.

42 Geyer JT, Ferry JA, Harris NL, Stone JH, Zukerberg LR, Lauwers GY, et al. Chronic sclerosing sialadenitis (Küttner tumor) is an IgG4-associated disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34:202-210.

43 Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Ohara M, Suzuki C, Naishiro Y, Yamamoto H, et al. A new conceptualization for Mikulicz's disease as an IgG4-related plasmacytic disease. Mod Rheumatol 2006;16:335-340.

44 Yamamoto M, Ohara M, Suzuki C, Naishiro Y, Yamamoto H, Takahashi H, et al. Elevated IgG4 concentrations in serum of patients with Mikulicz's disease. Scand J Rheumatol 2004;33: 432-433.

45 Miyajima N, Koike H, Kawaguchi M, Zen Y, Takahashi K, Hara N. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis associated with IgG4-positive-plasmacyte infiltrations and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Int J Urol 2006;13:1442-1444.

46 Ohtsubo K, Watanabe H, Tsuchiyama T, Mouri H, Yamaguchi Y, Motoo Y, et al. A case of autoimmune pancreatitis associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis. JOP 2007;8:320-325.

47 Stone JR. Aortitis, periaortitis, and retroperitoneal fibrosis, as manifestations of IgG4-related systemic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011;23:88-94.

48 Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:589-596.

49 Saeki T, Nishi S, Ito T, Yamazaki H, Miyamura S, Emura I, et al. Renal lesions in IgG4-related systemic disease. Intern Med 2007;46:1365-1371.

50 Zen Y, Kasahara Y, Horita K, Miyayama S, Miura S, Kitagawa S, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the breast in a patient with a high serum IgG4 level: histologic similarity to sclerosing pancreatitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:275-278.

51 Shrestha B, Sekiguchi H, Colby TV, Graziano P, Aubry MC, Smyrk TC, et al. Distinctive pulmonary histopathology with increased IgG4-positive plasma cells in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: report of 6 and 12 cases with similar histopathology. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1450-1462.

52 Saeki T, Saito A, Hiura T, Yamazaki H, Emura I, Ueno M, et al. Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of multiple organs with immunoreactivity for IgG4: IgG4-related systemic disease. Intern Med 2006;45:163-167.

53 Cheuk W, Yuen HK, Chu SY, Chiu EK, Lam LK, Chan JK. Lymphadenopathy of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:671-681.

54 Komatsu K, Hamano H, Ochi Y, Takayama M, Muraki T, Yoshizawa K, et al. High prevalence of hypothyroidism in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:1052-1057.

55 Yoshimura Y, Takeda S, Ieki Y, Takazakura E, Koizumi H, Takagawa K. IgG4-associated prostatitis complicating autoimmune pancreatitis. Intern Med 2006;45:897-901.

56 Zhang L, Smyrk TC. Autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related systemic diseases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2010;3:491-504.

57 Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Sano H, Ando T, Imai H, Takada H, et al. Difficulty in diagnosing autoimmune pancreatitis by imaging findings. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:99-108.

58 Members of the criteria committee for autoimmune pancreatitis of the Japan Pancreas Society. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis by the Japan Pancreas Society. J Jpn Pancreas 2002;17:587.

59 Choi EK, Kim MH, Kim JC, Han J, Seo DW, Lee SS, et al. The Japanese diagnostic criteria for autoimmune chronic pancreatitis: is it completely satisfactory? Pancreas 2006;33: 13-19.

60 Okazaki K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Naruse S, Tanaka S, Nishimori I, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria of autoimmune pancreatitis: revised proposal. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:626-631.

61 Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Zhang L, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1010-1016.

62 Chari ST. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis using its five cardinal features: introducing the Mayo Clinic's HISORt criteria. J Gastroenterol 2007;42:39-41.

Received March 30, 2011

Accepted after revision August 10, 2011

Author Affiliations: Second Surgical Propedeutical Department, Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Hippocration Hospital, Konstantinoupoleos 49, 54642 Thessaloniki, Greece (Psarras K, Baltatzis ME, Pavlidis ET, Lalountas MA, Pavlidis TE and Sakantamis AK)

Theodoros E Pavlidis, Professor, A Samothraki 23, 542 48 Thessaloniki, Greece (Tel: +302310-992861; Fax: +302310-992932; Email: pavlidth@med.auth.gr)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(11)60080-5

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2011年5期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2011年5期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Corticosteroids or non-corticosteroids: a fresh perspective on alcoholic hepatitis treatment

- Protective effect of probiotics on intestinal barrier function in malnourished rats after liver transplantation

- Naproxen-induced liver injury

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Salvianolic acid B modulates the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes in HepG2 cells

- Evaluation outcomes of donors in living donor liver transplantation: a single-center analysis of 132 donors