Primary biliary cirrhosis in Brunei Darussalam

Vui Heng Chong, Pemasiri Upali Telisinghe and Anand Jalihal

Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

Original Article / Biliary

Primary biliary cirrhosis in Brunei Darussalam

Vui Heng Chong, Pemasiri Upali Telisinghe and Anand Jalihal

Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam

BACKGROUND:Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is an uncommon autoimmune cholestatic disease that predominantly affects women. Certain human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) have been reported to be associated with susceptibility for PBC. We describe the profiles of PBC in Brunei Darussalam.

METHODS:All patients with PBC (n=10) were identified from our prospective databases. The HLA profiles (n=9, PBC) were compared to controls (n=65) and patients with autoimmune hepatitis (n=13, AIH).

RESULTS:All patients were women with a median age of 51 years (27-83) at diagnosis. The prevalence rate of the disease was 25.6/million-population and the estimated incidence rate varied from 0 to 10.3/million-population per year. Chinese (41.15/million) and the indigenous (42.74/million) groups had higher prevalence rates compared to Malays (22.62/ million). The prevalence among female population was 54.6/ million-population. All patients were referred for abnormal liver profiles. Five patients had symptoms at presentations: jaundice (20%), fatigue (20%), arthralgia (30%) and pruritus (20%). Serum anti-mitochondrial antibody was positive in 80% of the patients. Overlap with AIH was seen in 30%. Liver biopsies (n=8) showed stagei(n=2), II (n=4) and III (n=2) fibrosis. There were no significant differences in the HLA profiles between PBC and AIH. Compared to the controls, PBC patients had significantly more HLA classialleles specifically B7 (P=0.003), Cw7 (P=0.002) and Cw12 (P=0.007) but not the class II alleles. At a median follow-up of 23.5 months (2 to 108), all patients were alive without evidence of disease progression.

CONCLUSIONS:PBC is also a predominant female disorder in our local setting and most had mild disease. The HLA profiles of our patients were different to what have been reported.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010; 9: 622-628)

primary biliary cirrhosis; cholestasis; chronic liver disease; human leukocyte antigen; Southeast Asian

Introduction

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic cholestatic autoimmune disease of the liver of unknown etiologies that affects predominantly middle aged females usually presenting between the fifth and seventh decade.[1]It is characterized by the presence of serum anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) against the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, an enzyme complex that is found in the mitochondria and the slow progressive destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver.[1]In the early stages of the disease, most patients are asymptomatic and may only have mild cholestatic liver profiles.

Like many other conditions, both genetic and environmental factors have important roles in the development of PBC.[2,3]The human leukocytes antigens (HLAs) DRB1*08 and DRB1*12 have been reported to predispose to the development of PBC whereas DRB1*11 and DRB1*13 are protective according to studies in the Western populations.[4]However, other studies have not found such associations. Therefore some genetic associations may be population or ethnic specific.[5]Data on PBC in the Southeast Asia region are still limited.[6-10]We present the clinical and HLA profiles of our patients with PBC in Brunei Darussalam, a Malay predominant developing nation.

Methods

All the patients diagnosed and followed up for PBC were identified from three prospective databases: i) the hepatology clinics register; ii) the Department of Pathology register; and ii) the central pharmacy database. They were identified to those who were prescribed ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). We also contacted hepatologists at the other district hospitals who were involved in looking after patients with hepatic disordersto ensure no patients who might have been missed from the registries reviews. In our local setting, all patients with hepatic abnormalities are usually referred to two main referral centers for evaluations (RIPAS Hospital and Suri Seri Begawan Hospital). Only those who do not have any significant abnormalities are referred back to the outpatient clinics for further management.

Diagnosis of PBC was based on the established criteria: the presence of consistent clinical symptoms and abnormal liver profiles, positivity for serum AMA (≥1∶40) and histological changes consistent with PBC.[11]Patients were categorized into definite diagnosis for PBC if all three criteria were present or probable diagnosis if only two of three criteria were present. Other causes of cholestatic abnormal liver profiles such as medications, ingested supplements, stones diseases and other causes were excluded. Ultrasound scans of the abdomen were done to exclude other causes such as gallstones diseases or any space occupying lesions. Serum viral markers (HBsAg and HCV IgG) and serum auto-antibodies (anti-nuclear [ANA] and anti-smooth muscle [SMA) antibodies] were routinely done. Patients were treated with ursodeoxycholic acid (dose ranging from 10-15 mg/kg daily) with or without other immuno-suppressants (prednisolone or azathioprine), depending on whether there is overlap with autoimmune disease.

Clinical information on the patients was assessed in detail using pre-designed proforma for data collections. Data on demography (age, gender and race), presentations, treatments and outcomes were retrieved from detailed case notes review. Laboratory investigations (viral serology, liver function test, clotting profiles, full blood counts and autoimmune markers) were retrieved from the hospital computerized laboratory system. For the purpose of this study, histology of all the liver biopsies (n=8) were retrieved and reassessed by a single pathologist. The histology was graded with the established Scheuer scoring system.[12]

The HLA classialleles and class II specific alleles were tested prospectively. These tests were carried out in collaboration with an established laboratory (Centre for Transfusion Medicine [Clinical Laboratory], Health Sciences Authority, Singapore). Classiantigens (HLA A, B and C) were tested using the complement dependent cytotoxic (CDC) method whereas the class II antigens (HLA DR/DQ) were tested using the polymerase chain reaction-sequence-specific oligonucleaotide technique (PCR-SSO). Consents were obtained from patients prior to testing. We collected data from the patients who were potential donors or who had HLA assessment for various medical conditions as controls for comparisons (n=65). We also compared the HLA profiles of PBC patients with those of our patients with autoimmune hepatitis (n=13).

We calculated the point prevalence by using the population estimate data (2007) obtained from the Population Census (Economic and Planning Unit, Ministry of Finance). This consisted of 390 000 overall with a breakdown of 206 900 for males and 183 100 for females. The ethnic breakdown consisted of the Malays 68%, Chinese 12%, Indigenous 6% and others 14%.

Data were coded and entered in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 10.0, Chicago, Ill, USA) for analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as median and range and categorical variables expressed as absolute number and percentage. We compared the HLA profiles of the PBC patients with those controls and patients with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). The Mann-WhitneyUtest, Fisher's exact or the Chi-squared test were used where appropriate. AP<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The overall prevalence was 25.6/million-population whereas the point prevalence specifically for females was 54.6/million-population. The estimated incidence rate varied from 0 to 10.3/million-population per year. Among the three main ethnic groups, the prevalence rates were 22.62/million for Malays, 41.15/million-population for Chinese and 42.74/million for the indigenous group. All of our patients were female with median age of 51 years (27-83 years) at diagnosis and the ethnicbreakdown was consistent with the national population breakdown (Table 1). Most of the cases were diagnosed in the last few years. There was a median delay of 11 months (range 1-107 months) from first detected abnormalities to diagnosis of PBC. All patients had co-morbid conditions and three had autoimmune disease; systemic lupus erythematosus (n=1), rheumatoid arthritis and Sjogren's syndrome (n=1) and grave's disease (n=1). Only one patient used medication (metoprolol) that had been reported to be associated with cholestatic liver abnormalities. Another used a traditional medication intermittently but many years ago.

Table 1. Demographics of patients

All patients were referred for evaluation of abnormal cholestatic liver profiles (Table 2), with fluctuation in30% and persistence in 70%. On examination, 5 (50%) patients showed symptoms such as jaundice (20%), fatigue (20%), arthralgia (30%) and pruritus (20%). None of our patients had decompensated liver disease.

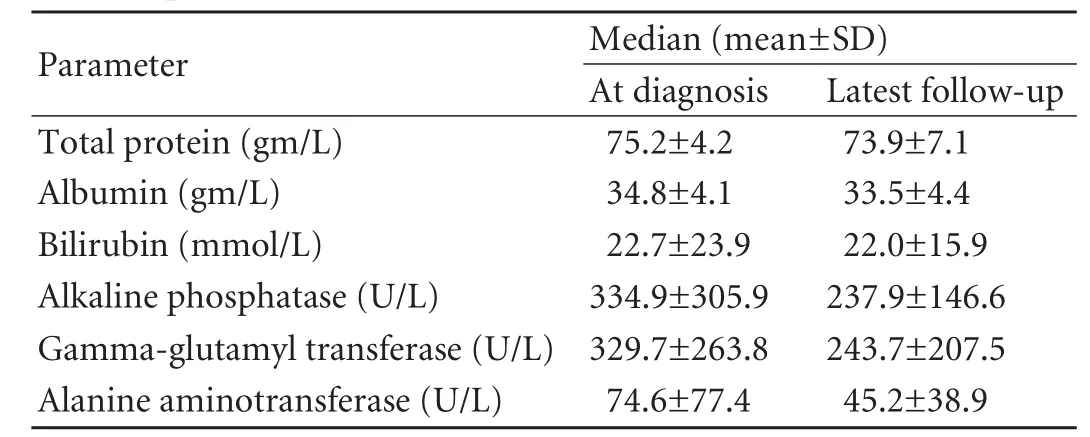

Table 2. Liver biochemical profiles of patients at diagnosis and last follow-up

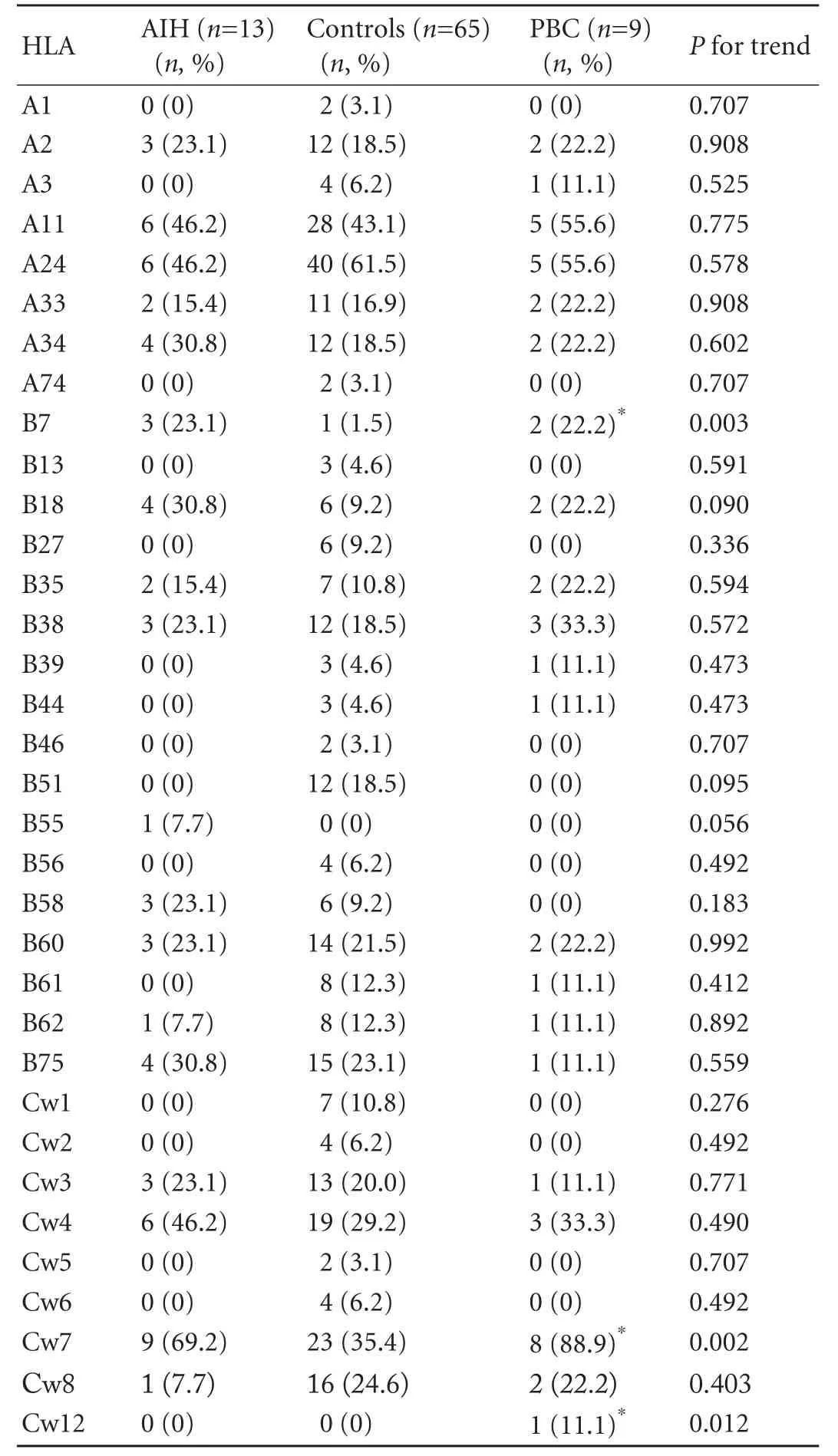

Table 3. Comparison of HLA class II alleles

Serum AMA was positive in 80% of the patients (median 1∶320; range 1∶80 to 1∶640) and positive at some points in 70%. Liver biopsies done in 8 patients showed stagei(n=2), II (n=4) and III (n=2) fibrosis. Based on histology and serum antibodies profiles, overlap with AIH was present in 30% of the patients.

All patients were treated with UDCA and showedbiochemical responses. At a median follow up of 23.5 months (range 2 to 108 months), the patients were well and latest biochemical profiles did not show any progression (Table 2) (allPvalues > 0.05).

Table 4. Comparisons of the HLA classiantigens between AIH patients and controls

There were 8, 17 and 9 alleles detected for HLA A, B and C classialleles respectively. In the class II alleles, 13 and 5 HLA DRB1 and DQB1 alleles were detected respectively. The most prevalent classialelles in patients with PBC were A11, A24 and Cw7, whereas DRB1*15, DQB1*05 were the most prevalent class II antigens (Tables 3 and 4). Compared with patients with AIH, PBC patients demonstrated no significant differences except slightly less DRB1*04 (P=0.083) and DQB1*06 (P=0.066) and more DRB1*07 (P=0.075) and DRB1*14 (P=0.075). Compared with the controls, PBC patients had more HLA B7 (P=0.003), Cw7 (P=0.002), Cw12 (P=0.007), DRB1*16 (P=0.097), DRB5 (P=0.091) but less DBQ1*06 (P=0.080).

Discussion

PBC is reported to be less common in Asians than in the Westerners, which but have the same natural history.[10,13-15]Earlier studies reported lower rates of PBC, which have been reported to be increasing in recent years.[16-19]The increase has been attributed to increasing awareness, better detection and more rigorous epidemiological studies. This is also true in our setting as most of the cases have been diagnosed in the last few years.

The reported prevalence rates in Western contries were estimated to be between 6.7/million and 940/ million population with the later figure representing the prevalence rate for women of more than 40 years old in the United Kingdom. The estimated annual incidence is between 0.7/million and 49/million population per year.[16-21]The highest rates are in the northern hemispheres in countries like the United Kingdom,[16]Scandinavia (In Sweden the prevalence of 151/million and the mean annual incidence of 13.3/million, in Finland: 103/million in 1988 and 180/ million in 1999),[17,20]Canada (an age adjusted annual incidence of 30.0/million and a prevalence of 227/ million in 2002)[18]and the United States (Minnesota: an age adjusted incidence of 27/million and an adjusted prevalence of 402/million; Alaska: a prevalence of 160/million).[19,21]Among the Caucasian population, the lowest rate has been reported from Australia (a prevalence of 19.1/million and a higher prevalence in women of 24 years old with 51/million).[22]To date, there are little or no data available on the rates in the Asia Pacific region. The prevalence, incidence and rate of the disease in the female population in the present study were much lower those reported in the western countries. Interestingly, these results are comparable to those reported from Australia. However, this study was reported more than 15 years ago. Among the different ethnic groups, both our Chinese (41.15/million) and Indigenous (42.74/million) populations had rates almost twice of the Malays (22.62/million), indicating genetic predispositions. None of the previously reported studies from the Southeast Asia had reported the prevalence and incidence rates as most studies were center-based, not population based.[6-10]Given the similarities in the population demographic and genetic make up in some nations of the Southeast Asia, especially Malaysia and Singapore, it is very likely that their prevalence and incidence rates will be comparable to what we have reported.

The profiles of our patients are in agreement with previous reports from our region and the rest of the world.[6-10]All our patients were females with a median age of 51 years at diagnosis of the disease. A recent study from Singapore showed that 97% of the affected were females with a mean age of 55 years at diagnosis and 81% were positive for AMA.[10]Other two earlier studies from Singapore both in small case series also showed similar characteristics. To date, there are only two studies that specifically looked at PBC in a predominant Malay population.[6,7]The first study based on seven patients over a 12-year period showed that all of the affected were female Chinese with age ranging from 30 to 55 years. The later study identified 17 cases in a period of 8 years with a female to male ratio of 3.25∶1 and mean age of 45.9 years (range 14 to 67 years ) at presentation. Both studies showed that Chinese were at higher risk and a majority of them were symptomatic (jaundice, fatigue and pruritus) at presentation.[6,7]Our study also showed ethnic differences. Studies from other parts of Asia other than Southeast Asia have also reported similar findings.[13,14,23]

The clinical manifestations of PBC have changed from predominantly symptomatic to asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Fifty percent of our patients were asymptomatic and interestingly even among those with symptoms; their symptoms were not the main reason for referrals. The spectrums of symptoms attributable to PBC were also comparable to the reported rates. Interestingly, none of our patients had advanced or decompensated liver disease at diagnosis. Unlike earlier studies that showed advanced disease at diagnosis, a recent study from Singapore reported that 50% of the patients were asymptomatic at diagnosis.[8-10]This change has largely been attributed to earlier diagnosis.In many regions, however, a large proportion of patients with PBC is still diagnosed at advanced stage of the disease depending on the health care coverage, and patients' health seeking behaviors. Ethnic background has also associated with differences in the disease profiles. In the United States, non-Caucasian patients are more likely to have advanced liver disease at diagnosis.[24]Similarly, an Indian study showed that Indian patients have advanced diseases (40%) and are diagnosed at younger ages.[23]

Most patients will progress with follow-up, more rapid in those who are symptomatic at diagnosis. After a median follow-up of approximately 2 years, none of our patients had evidence of disease progression. However, the duration of follow-up in our study was short. In a study from Singapore, disease progressions were noted in 15.6% and 31% of the patients at 5 and 10 years respectively.[10]Serum bilirubin level, prothrombin time, albumin, alkaline phosphatase and high density lipoprotein (HDL) at the time of diagnosis were shown to be predictive factors of disease progression. Not surprisingly, in the Mayo natural history model, age, serum bilirubin and albumin, prothrombin time, presence or absence of ankle edema and diuretics were used to predict survival without treatment. Use of UDCA especially in the early stages has been shown to cause biochemical improvement and even histological regression. However, controversies remain as other studies have not found similar findings.

Genetic factors have been reported to be important. Familial predisposition for PBC among first degrees relatives has been estimated to be around 5%.[25]Genetic predisposition has been reported to be related to maternally inherited factors and to present in the second generations being most common in motherdaughter or sister-sister combination.[26,27]Concordance has been shown to be higher among monozygotic twins with similar age of onset of disease but differences in the natural history and disease severity.[28]This suggests the importance of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of PBC.

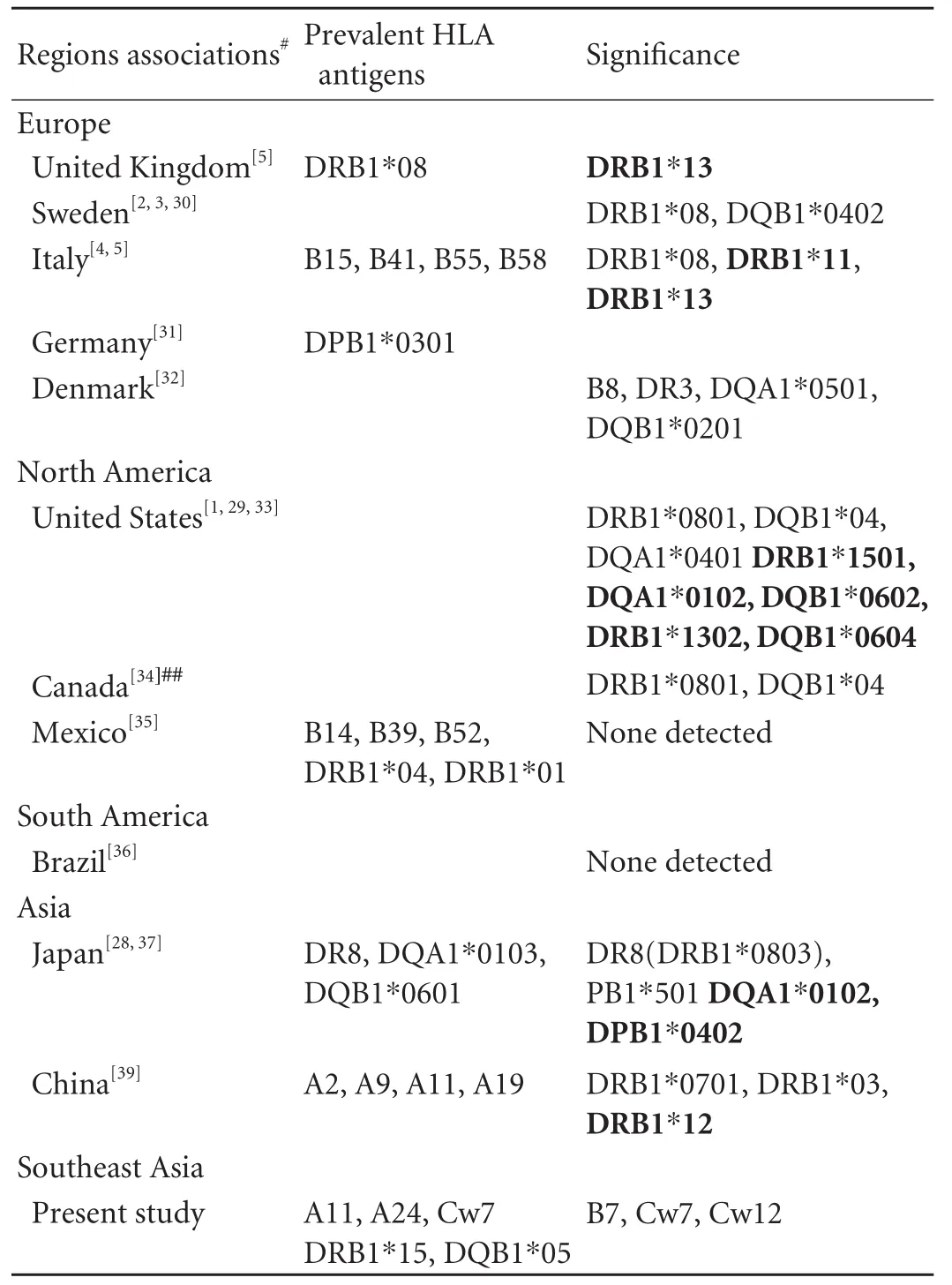

HLA DRB1*08 and DRB1*12 predispose to the development of PBC, whereas DRB1*11 and DRB1*13 are protective according to the studies on the Caucasians populations.[4]Other studies based on different populations have not reported such findings but different protective and predisposing alleles (Table 5).[2-4,29-39]To date, most studies on the HLA association from the Asia Pacific region come from Japan. In Japan, HLA DR1*08 association has also been reported but it is weaker. HLA DQA1*0102 has also been shown to be protective.[37,38]A Chinese study revealed that only HLADRB1*0701 was significantly associated with PBC.[39]To date, there has been no study on the profiles of PBC among Malay patients. Compared to the control group, our PBC patients had significantly more HLA B7, Cw7 and Cw12. Among the class II antigens, DRB1*16 and DRB5 were more common and DQB1*06 was less but all of these were not significant. Interestingly, a study on Caucasian patients with PBC showed that the genetic predisposition between AMA-positive and AMA-negative PBC may be different.[34]HLA-DRB1*08 and DQB1*04 were found in the AMA-positive PBC patients but not in AMA-negative patients. The importance of classiantigens is unknown.

Table 5. Reported HLA antigens and association with PBC

It is clear that there are strong genetic predispositions to PBC. However, it is also clear that there are differences between different populations. As moresensitive tests are developed, more associations will be found with newer and more specific alleles, making the roles of HLA in PBC more complex. Generally, some genetic associations may be population or ethnic specific.[5]Therefore, use of HLA markers in PBC should be tailored depending on regions as well as ethnicity and genetic background of patients.

Compared to AIH, another autoimmune disorder, we did not find any significant differences in the present study. HLA DR3 (DRB1*0301) and DR4 (DRB1*0401) are reported to be very common in AIH, in particular DR3.[40]Therefore, the HLA predisposition to PBC seems to be completely different to AIH.

The main limitation in our study is the small sample size. However, we believe that the number is true as the overall population of our country is small. The calculated rates that we were found were comparable to the reported rates. The main strength of our paper is the ability to capture the data from the whole population. If several reliable databases were sued, it would not have missed any cases under follow-up.

In conclusion, the prevalence rates of PBC in our country are comparable to the reported rates. Most of the PBC cases are diagnosed at the early stages and are asymptomatic as diagnosed by evaluation of abnormal liver profiles. The overall profiles are also comparable to those reported in the literature. However, the HLA profiles are different to those of Caucasian patients.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:CVH and JA conceived the idea for the study. CVH collected, analyzed, interpreted the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TPU assessed the histology. All authors approved the final manuscript. CVH is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1261-1273.

2 Selmi C, Lleo A, Pasini S, Zuin M, Gershwin ME. Innate immunity and primary biliary cirrhosis. Curr Mol Med 2009; 9:45-51.

3 Selmi C, Gershwin ME. The role of environmental factors in primary biliary cirrhosis. Trends Immunol 2009;30:415-420.

4 Invernizzi P, Selmi C, Poli F, Frison S, Floreani A, Alvaro D, et al. Human leukocyte antigen polymorphisms in Italian primary biliary cirrhosis: a multicenter study of 664 patients and 1992 healthy controls. Hepatology 2008;48:1906-1912.

5 Donaldson PT, Baragiotta A, Heneghan MA, Floreani A, Venturi C, Underhill JA, et al. HLA class II alleles, genotypes, haplotypes, and amino acids in primary biliary cirrhosis: a large-scale study. Hepatology 2006;44:667-674.

6 Kananathan R, Suresh RL, Merican I. Primary biliary cirrhosis at Hospital Kuala Lumpur: a study of 17 cases seen between 1992 and 1999. Med J Malaysia 2002;57:56-60.

7 Mohammed R, Goh KL, Wong NW. Primary biliary cirrhosis--experience in University Hospital, Kuala Lumpur. Med J Malaysia 1996;51:99-102.

8 Chong RS, Ng HS, Seah CS. Primary biliary cirrhosis: a description of four cases. Singapore Med J 1988;29:68-71.

9 Yap I, Wee A, Tay HH, Guan R, Kang JY. Primary biliary cirrhosis--an uncommon disease in Singapore. Singapore Med J 1996;37:48-50.

10 Wong RK, Lim SG, Wee A, Chan YH, Aung MO, Wai CT. Primary biliary cirrhosis in Singapore: evaluation of demography, prognostic factors and natural course in a multi-ethnic population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23: 599-605.

11 Heathcote EJ. Management of primary biliary cirrhosis. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines. Hepatology 2000;31:1005-1013.

12 Scheuer P. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Proc R Soc Med 1967;60: 1257-1260.

13 Wong GL, Law FM, Wong VW, Hui AY, Chan FK, Sung JJ, et al. Health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23: 592-598.

14 Su CW, Hung HH, Huo TI, Huang YH, Li CP, Lin HC, et al. Natural history and prognostic factors of primary biliary cirrhosis in Taiwan: a follow-up study up to 18 years. Liver Int 2008;28:1305-1313.

15 Farrell GC. Primary biliary cirrhosis in Asians: less common than in Europeans, but just as depressing. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:508-511.

16 James OF, Bhopal R, Howel D, Gray J, Burt AD, Metcalf JV. Primary biliary cirrhosis once rare, now common in the United Kingdom? Hepatology 1999;30:390-394.

17 Rautiainen H, Salomaa V, Niemelå S, Karvonen AL, Nurmi H, Isoniemi H, et al. Prevalence and incidence of primary biliary cirrhosis are increasing in Finland. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:1347-1353.

18 Myers RP, Shaheen AA, Fong A, Burak KW, Wan A, Swain MG, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cirrhosis in a Canadian health region: a populationbased study. Hepatology 2009;50:1884-1892.

19 Kim WR, Lindor KD, Locke GR 3rd, Therneau TM, Homburger HA, Batts KP, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cirrhosis in a US community. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1631-1636.

20 Danielsson A, Boqvist L, Uddenfeldt P. Epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis in a defined rural population in the northern part of Sweden. Hepatology 1990;11:458-464.

21 Hurlburt KJ, McMahon BJ, Deubner H, Hsu-Trawinski B, Williams JL, Kowdley KV. Prevalence of autoimmune liver disease in Alaska Natives. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2402-2407.

22 Watson RG, Angus PW, Dewar M, Goss B, Sewell RB, Smallwood RA. Low prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis in Victoria, Australia. Melbourne Liver Group. Gut 1995;36: 927-930.

23 Sarin SK, Monga R, Sandhu BS, Sharma BC, Sakhuja P, Malhotra V. Primary biliary cirrhosis in India. HepatobiliaryPancreat Dis Int 2006;5:105-109.

24 Peters MG, Di Bisceglie AM, Kowdley KV, Flye NL, Luketic VA, Munoz SJ, et al. Differences between Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic patients with primary biliary cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology 2007;46:769-775.

25 Jones DE, Watt FE, Metcalf JV, Bassendine MF, James OF. Familial primary biliary cirrhosis reassessed: a geographically-based population study. J Hepatol 1999;30: 402-407.

26 Brind AM, Bray GP, Portmann BC, Williams R. Prevalence and pattern of familial disease in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut 1995;36:615-617.

27 Bittencourt PL, Farias AQ, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Goncalves LL, Goncalves PL, Magalhães EP, et al. Prevalence of immune disturbances and chronic liver disease in family members of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;19:873-878.

28 Selmi C, Mayo MJ, Bach N, Ishibashi H, Invernizzi P, Gish RG, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: genetics, epigenetics, and environment. Gastroenterology 2004;127:485-492.

29 Mullarkey ME, Stevens AM, McDonnell WM, Loubière LS, Brackensick JA, Pang JM, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class II alleles in Caucasian women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Tissue Antigens 2005;65:199-205.

30 Wassmuth R, Depner F, Danielsson A, Hultcrantz R, Lööf L, Olson R, et al. HLA class II markers and clinical heterogeneity in Swedish patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Tissue Antigens 2002;59:381-387.

31 Mella JG, Roschmann E, Maier KP, Volk BA. Association of primary biliary cirrhosis with the allele HLA-DPB1*0301 in a German population. Hepatology 1995;21:398-402.

32 Morling N, Dalhoff K, Fugger L, Georgsen J, Jakobsen B, Ranek L, et al. DNA polymorphism of HLA class II genes in primary biliary cirrhosis. Immunogenetics 1992;35:112-116.

33 Begovich AB, Klitz W, Moonsamy PV, Van de Water J, Peltz G, Gershwin ME. Genes within the HLA class II region confer both predisposition and resistance to primary biliary cirrhosis. Tissue Antigens 1994;43:71-77.

34 Stone J, Wade JA, Cauch-Dudek K, Ng C, Lindor KD, Heathcote EJ. Human leukocyte antigen Class II associations in serum antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA)-positive and AMA-negative primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2002;36: 8-13.

35 Vázquez-Elizondo G, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez N. Human leukocyte antigens among primary biliary cirrhosis patients born in Mexico. Ann Hepatol 2009;8:32-37.

36 Bittencourt PL, Palácios SA, Farias AQ, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Cançado EL, Carrilho FJ, et al. Analysis of major histocompatibility complex and CTLA-4 alleles in Brazilian patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;18:1061-1066.

37 Onishi S, Sakamaki T, Maeda T, Iwamura S, Tomita A, Saibara T, et al. DNA typing of HLA class II genes; DRB1*0803 increases the susceptibility of Japanese to primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1994;21:1053-1060.

38 Seki T, Kiyosawa K, Ota M, Furuta S, Fukushima H, Tanaka E, et al. Association of primary biliary cirrhosis with human leukocyte antigen DPB1*0501 in Japanese patients. Hepatology 1993;18:73-78.

39 Liu HY, Deng AM, Zhou Y, Yao DK, Xu DX, Zhong RQ. Analysis of HLA alleles polymorphism in Chinese patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2006;5:129-132.

40 Czaja AJ, Freese DK; American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2002;36:479-497.

April 26, 2010

Accepted after revision August 21, 2010

Author Affiliations: Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Department of Medicine (Chong VH and Jalihal A) and Department of Pathology (Telisinghe PU), Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha (RIPAS) Hospital, Bandar Seri Begawan BA 1710, Brunei Darussalam

Vui Heng Chong, MRCP, FAMS, FRCP, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Department of Medicine, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha (RIPAS) Hospital, Bandar Seri Begawan BA 1710, Brunei Darussalam (Tel: +673 8778218; Fax: +673 2242690; Email: chongvuih@yahoo.co.uk)

© 2010, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2010年6期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2010年6期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

- Ileal loop interposition: an alternative biliary bypass technique

- Letters to the Editor

- Preventive effects of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell implantation on intrahepatic ischemic-type biliary lesion in rabbits

- Expression of Ezrin, HGF, C-met in pancreatic cancer and non-cancerous pancreatic tissues of rats

- Toll-like receptor 4-mediated apoptosis of pancreatic cells in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in mice