Contemporary Landscape Painting

WU BING

The landscape painting, along with figure painting and bird-and-flower painting, constitute the most important categories of Chinese paintings.

It was the tenth anniversary of the Peoples Republic of China in 1959 when the Great Hall of the People to the west of Tiananmen Square was unveiled. As a venue for national leaders to meet their foreign counterparts, the hall needed a large work of art to represent the country. Fu Baoshi (1904-1965) and Guan Shanyue (1912-2000), two of Chinas most respected and renowned painters, were commissioned to create such a work for the space. Zhou Enlai (1898-1976), premier at the time, identified the theme – a line from Chairman Mao Zedongs poem, “This land is so rich in beauty.”

After completing several studies, the two masters finally finished the work two months later. In the painting, the sun is shining over vibrantly green pines. Mountains in the foreground represent South China, and a sea of clouds and snow-capped mountains in the background represent North China. Through the middle run the Yangtze and Yellow rivers that add an integral geographic touchstone to the painting. The work really impressed everyone, including Mao, who agreeably wrote his inspirational line on it.

The painting is nine by five and a half meters in size, and as many as 41 assistants were marshaled to render it. They were divided into several teams to prepare. Some made one meter long brush-pens, and some joined sheets of rice paper together. Another special team was in charge of ink-grinding,rubbing ink sticks against inkstones round the clock.

Defying Reason in Ink and Wash

From the perspective of classical Western landscape painting, its unreasonable to see scenes that are thousands of miles apart in one work. Since Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) invented geometric optical linear perspective, his theory was widely applied in Western studios, giving a spacious and realistic feel to paintings and making landscapes akin to panoramic photography.

But landscape painting in China developed in a quite different way – a viewpoint which can be moved if necessary. The “cavalier” perspective, as some theorists called it, is difficult for Westerners to comprehend.

Even novice Chinese painters were often confused by the technique. Liu Zhenduo, now a mainstay artist, was once among them. In 1963, the 20-something Liu accompanied Fu Baoshi and Guan Shanyue on a field sketching expedition. Fu used to go out in the morning with a sketch book and come back to detail his drawings in the evening. One of these works astonished Liu – a church, apparently Western style, dominating the scene of a Chinese countryside. The church never existed in that area, but Fu explained with delight, “I borrowed it from Romania.” Liu suddenly understood landscapes could be composed of scenes amalgamating different places or times. Measured by artistic standards familiar to Westerners, landscapes like Fus would be characterized as surrealism: symbolic content and romantic theme. This Land is So Rich in Beauty is an excellent illustration of this.

Shrugging Off the World

The scenes in Chinese landscapes are not a literal rendering of specific mountains or rivers, but a painters personal re-creation. Shi Tao (1630-1724), an artist laying claim to innovation, once said: “I have sketched not one, but all beautiful peaks for my creation.”

The landscape painting embodies typical Chinese views on nature and life. Pursuing “harmony between man and nature,” people in ancient times believed that humanity is part of nature. This idea was first formed about 2,500 years ago. In the late Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), Li Er, or Lao Zi as he was known by later generations, advocated retirement from public life to the countryside to achieve a simple and happy existence. As one of the greatest philosophers in ancient China, he enjoyed equal popularity with Confucius. Getting tired of the pressure brought by work and fame, people are likely to turn to Lao Zis maxim – give up all striving for gain, and go back to nature. For many Chinese, the landscape painting represents an idyllic life, free from worldly concerns.

Lao Zis doctrines evolved into Daoism, a religion of the late Eastern Han (AD 25-220). Its followers believed they could become immortal if they lived a simple life and diligently practiced in remote mountains. From that time on, imposing mountains, pines and cypress, waterfalls and creeks were commonly depicted in landscape paintings, and regarded as representations of a fairyland.

In the Song Dynasty, landscape artist Guo Xi (AD 1000-1090) even put forward a standard for this landscape fairyland – a good painting should give viewers the feeling that they can walk, live and travel in it.

Darlings of the Auction

The value of these paintings is quite real.In July 2006, Fu Baoshis Ode to Rainflower Terrace was auctioned for RMB 46.2 million, a record price for contemporary landscape paintings.

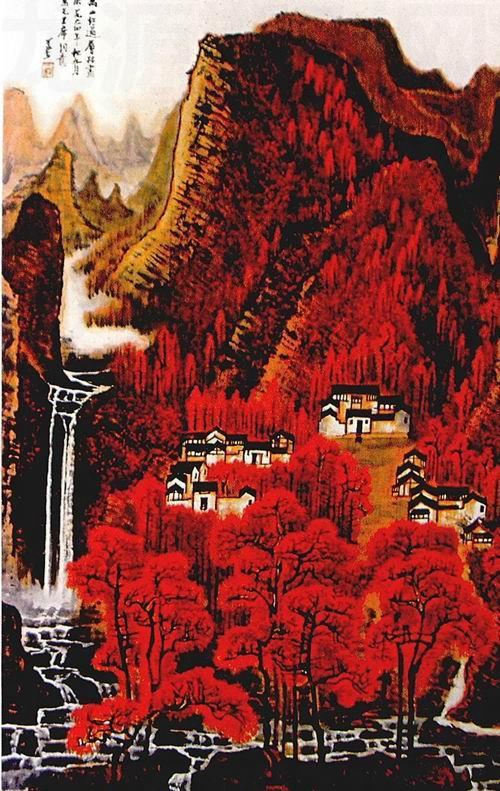

About ten months later, Li Keran (1907-1989)s work Ten Thousand Hills Crimsoned Through became a magnet at Hong Kong Christies. After rounds of bidding, it was sold for HK $35.04 million. From 1962 to 1964, Li created seven landscapes inspired by Chairman Maos famous line “I see a thousand hills crimsoned through, by their serried woods deep-dyed,” and this painting is the largest of the seven at 131 cm by 84 cm. Li painted with high-quality vermilion obtained from the stocks of the former royal family. With red as the basic color, the landscape merges hues that suggest joy as well as tranquility. This exquisite masterpiece fully reflects his formidable skills.

As a living icon of Chinese art, Li always deprecated himself with the title “swot” – a student who sweats, or must apply himself ardently to his subject. He believed the process of learning landscape painting was a steep challenge and that only the persistent achieved success. At an early age, Li received a comprehensive education in Western art. Then he started to learn from renowned Chinese painting masters, like Huang Binhong (1865-1955) and Qi Baishi (1864-1957), trying to integrate the Western artistic practice with Chinese traditions. With such disparity between the two schools, it was only wisdom and courage that helped painters find a balance. But Li finally succeeded and created a unique style of his own.

The final touch to any painting is the application of a seal or seals. Painters used to carve their names, artistic propositions or aphorisms on precious stones. In the 1950s, Li loved to use two seals – “Courage is valuable” and “In pursuit of the soul.” He explained later that it was courage that let painters break from set patterns, and the soul that embodies the spirit of an age. Believing all beautiful scenes of the motherland should be admired, he was determined to capture the richest content on paper. Li applied the Western sketching method to render shadows on mountains, and also pioneered the backlighting method. So his paintings of heavy black mountains do not lower the viewers spirit; you can always spot rays of light outlining the stone faces, as well as waterfalls and houses nestled in deep forest. His style went mainstream in the last two decades of the 20th century.