The Road from Communal to Owned Housing

By WU NA

Homes in China have transitioned during the past sixty years from government-allocated to commercial housing. The change has brought immense improvements to peoples living conditions.

Waiting for Welfare Housing

The novel The Happy Life of Talkative Guy Zhang Damin by Liu Heng, an account of the real lives of everyday Beijing residents, won the Lao She Prize for Literature. The main character is Zhang Damin. He, his widowed mother and four siblings share a crowded quadrangle with several other families. Their living room is also their bedroom. In it are one double and one single bed, a desk, a folding table, a washstand and a few stools – the extent of the family furniture. The inner room is the width of a train sleeping compartment.

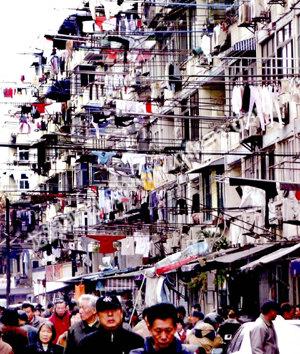

Residential conditions in the 1980s were often even worse than those depicted of the character Zhang Damin and his family. As Chinas population skyrocketed after the 1950s, formerly one-household quadrangle houses were often occupied by dozens of families. Each lived in one room and all shared a toilet, courtyard and whatever other facilities existed. The common people of Shanghai lived in similarly poor conditions in shikumen or tenement housing.

Zhang Damins story describes how, after Zhang and his brother marry, everyday life in the 16 sq meter room deteriorates from being cramped to downright embarrassing. Zhang Damin has no choice but to build a room around the pomegranate tree in the small yard. He names his son shu which means tree in Chinese.

The old saying, “a good neighbor is better than a brother in the next village,” defines the close bond among residents of neighborhoods composed of crowded quadrangles. But bonding does not always compensate for the absence of personal privacy under these conditions.

People sharing a quadrangle envied those living in the storied dwellings of the time. These basic tubular apartments were originally student and worker dormitories which gradually evolved into family residences whose tenants used public toilets and bathrooms. Each family had a small stove outside their room, and at mealtimes the corridor transformed into a mass kitchen.

People living in individual apartments were regarded as highly privileged, by virtue of their 30 to 50 sq meter area and self-contained kitchen and toilet.

Government housing was formerly an aspect of social welfare. But the time lapse between applying for and actually moving into a place of ones own could be anything from a few years to a whole lifetime, even when fulfilling the requirements of preferred occupation and married status. At first only married cadres qualified for allocated housing. Many people would wed for the express purpose of having their own home. The alternative was living with parents or colleagues. Candidates for housing assignments were ranked according to work, seniority, and any commendations, such as performance rewards. But these requirements often changed.

Before 1949, 70 percent of urban families lived three-to-five people under one tiled roof. Upon establishment of the Peoples Republic of China the government priority was on production rather than consumption and life quality; there was consequently low residential investment. From 1949 to 1978, the government expended RMB 37.4 billion on residential construction, which worked out to less than RMB 10 per capita per year. During this period, the total residential area in cities and towns was just 500 million sq meters. In the early years after the founding of new China, the per-capita living space was 4.5 sq meters. But by 1978 this had fallen to 3.6 sq meters. Half of the urban population lacked adequate housing.

Goodbye to Welfare Housing

Housing reform soon became imperative, as people could not properly function in these wanting living conditions.China tried various methods of housing reform, following the examples of Singapore and Britain of raising rentals and selling ownership, according to Gu Yunchang, vice president of China Real Estate and Housing Research Association. Given the relatively low salaries at the time, however, the government finally decided to carry out thoroughgoing property rights reform.

Since 1980, Chinese citizens have been allowed to build and purchase housing individually. But even though the price of housing was initially just RMB 120 to 150 per sq meter, few people showed interest. One reason was their aversion to the idea of owner-occupied homes. Another was that to common people buying a home seemed a huge financial transaction, even though they needed to pay just one third of the purchase price, according to the new policy.

Chinas real estate made little headway until Deng Xiaopings Southern Inspection Tour of 1992, when he urged the people to follow the example of the Pearl River Delta and stimulate economic development (according to the landmark legislation allowing legal persons to transact land use rights). Realty investment soon doubled that of the same period the previous year. The average housing prices grew so rapidly that the government adopted macroeconomic regulations as a means of control.

Housing reform began six years later. Commercialized housing ended the welfare-oriented public housing distribution system, and real estate investment surged, becoming an important economic impetus in China. In the meantime, living conditions rapidly improved. The per capita building area of the registered population in cities and towns is now 28 sq meters according to figures from Qi Ji, vice minister of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. Taking into account migrant workers in urban areas, however, the figure is actually 22 sq meters per capita.

Li Changxiu, a 73-year-old retired worker, now lives in Beijings Wangjing District. In the 1980s he and the three generations of his eight other family members all lived in one room. Carried along by the reform and opening-up policy, his children went into business. Their former dwelling was demolished five years ago, and with the compensation he received plus his offsprings financial support, Li was able to buy the 120 sq meter apartment where he now lives. It would have been impossible under the former welfare housing allocation system for senior workers like Li to have such a large home. Li Changxiu is happy with the layout, ample light and large kitchen. The only drawback, Li says, is that the residential community is so large that Li and his wife sometimes lose their way home.

Private Space Is Costly

Statistics from the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development show that the rate of urban owner-occupied dwelling rate hit 83 percent in 2007. The reason for this was the huge number of “mortgage slaves” obliged to keep up regular monthly repayments. Urban residents usually purchased an apartment with their savings, or by means of the housing accumulation fund, housing allowances or housing loans. Sky-high housing prices placed immense pressure on everyday citizens. Many young home buyers were forced to seek help from their parents to supplement their savings. In 2007, the balance of personal loans in Chinese financial institutions was RMB 3.2 trillion, 80 percent of which comprised personal housing loans. Housing prices in Beijing shot up again in 2008, to the extent that the average annual salary was insufficient to buy less than two sq meters.

Hardest-hit are young wage-earners and people whose homes have been demolished for urban development. As they cannot afford to buy homes in a convenient location they have to consider cheaper housing on the city outskirts. Residential housing built since 2000 in Beijing is mainly located in suburban districts, having expanded from the Third Ring Road of 20 years ago to the Fifth Ring Road and even further out.

Living in the outskirts, however, is not comparable to the situation in developed countries, whereby the well-to-do often live in suburbs and the poor reside in the inner city. The situation is actually the reverse in China. Suburban residential areas where young wage-earners live are known as “sleeping blocks.” The people who make up this residential group spend most of their time either at work or commuting. By the time they get home they are too tired to do anything but sleep. Economist Wang Xiaoguang from the Academy of Macroeconomic Research under the National Development and Reform Commission predicts that low-income people who live in suburban areas will suffer even more from ever-heavier commuter traffic.

Home Ownership Scheme

Housing remains a crucial issue for low- to middle-income families and for the country in general. In 1994, the government began to build affordable housing to ease the problems of this demographic group. Cheaper than the market price, it is in huge demand, which is why eligible purchasers are selected by lucky draw.

In 2005, home-seekers waited in line outside housing sales offices, night and day one month in advance, in the hope of obtaining a sequence number for affordable housing in Beijings suburbs. The presence among them of high-income earners raised loud protests and the issue of justice. Professor Yan Jinming from the School of Public Administration of Renmin University of China stated: “Affordable housing is for the benefit of the low- and middle-income group, but problems still exist. This scheme also puts a curb on escalating house prices.” Yan believes that there will soon be greater justice, transparency and efficiency in the system. Regulations regarding affordable housing, redefining qualified purchasers, standard layout and other details were instituted in 2007. Information on eligible applicants is also published in the media to ensure a just procedure.

More than 90 million sq meters ofaffordable housing was under construction in 2008, more than 60 million sq meters of which has been finished. The government also revealed plans to build four million apartments in the coming three years.

Since then the government has stipulated that annual land supply for low- and medium-priced housing and small- and medium-sized commercial housing (including affordable housing) and low-rent housing should be no less than 70 percent of the total residential land supply. By the end of 2006, 77.9 percent of cities in China had established low-rent housing systems and RMB 7.08 billion had been allocated to building low-rent housing. This move helped improve the living conditions of 547,000 low-income families.

More policies and regulations guaranteeing affordable housing for the low-income urban demographic group are in the process of establishment. The Measures for the Guarantee of Low-rent Homes, for example, stipulate that no less than 10 percent of revenues from the land grant fee be allocated to construction of low-rent housing. Guo Songhai, director of the Institute of Real Estate Economy, Shandong Economic University, has pointed out that the government is changing from the “market first, guarantee second” to “equal stress on both market and guarantee” principle first formulated in the housing reform of 1998.

A total of RMB 35.4 billion was invested in low-rent housing system in 2008 – 3.7 times that in 2007. This amount includes RMB 28.6 billion on housing construction and RMB 6.8 billion on subsidies. A total of 630,000 families have been provided with low-rent housing and 2.49 million low-income families have obtained government subsidies. The present system has basically solved the housing problems of families in financial difficulty.