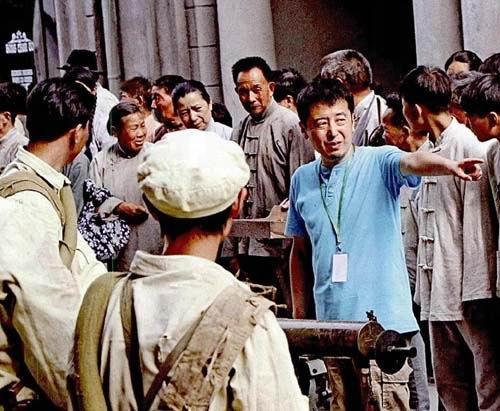

The City and Human Life: Jia Zhangke’s Thematic Films

By TANG YUANKAI

The shooting of Shanghai Legend, a wide-screen documentary film about Shanghai, wrapped this October after a three-year directorial marathon by Jia Zhangke. This will be his tribute to the 2010 Shanghai World Expo.

“I wanted to make a visual monument to Shanghai,” said Jia Zhangke. To him, the city has been at the center of every stage in Chinas urbanization, and its residents have been pioneers on every new frontier.

Curiously, in 1910, Shanghai novelist Lu Shie predicted in his work New China that China would host the World Expo in 2010. He also predicted that in 2010 Shanghai would have built its subways, bridges and sub-river tunnel to solve traffic problems. The visionary aspects of his novel may have been unintentional, but in light of the fact the World Expo is indeed to be held in Shanghai next year, it seems like miraculous fortune telling. Lu Zhenxiong, grandson of the author, now runs a photo studio in the port city. More than 100 Shanghai natives just like him appear in Shanghai Legend.

“As a matter of fact, I am not pleased about having the word ‘legend in the title, but theres no other option. Shanghai is legendary indeed,” admits the director. In his approach to the documentary, Jia Zhangke has adhered to his themes of “the city and human life.”

Art Imitates Life

His 2000 film Platform dealt with the struggles of a small rural performing troupe during the years when China was first overwhelmed by pop culture and consumer products after decades of islolation from the rest of the world. The story has little to do with a railway platform but is based on a popular song of the same title referring to a fresh start in a persons life. He wanted to create an epic about the common man, to highlight the great changes in the era. The plot unfolds in his hometown of Fenyang in Shanxi Province, in the 1980s. “This decade is unforgettable; I grew from 10 to 20 years of age then,” remembers Jia.

“When I was seven or eight years old, my elder brother said, ‘I would be the happiest man in the world if I could buy a motorcycle. Three or four years after that, motorcycles were everywhere in the street,” marvels Jia, and he recalls his surprise to encounter something called a washing machine, and later, his fascination when his family bought one. “Not so long before that there was little choice in products, even simple ones like books.By 1983 or 1984, even in remote and isolated places like Fenyang, Sigmund Freud, Friedrich Wilhelm and Nietzsche could be found in book stalls.”

Shanxi is a provincial backwater in China, and Fenyang a small place nested deep within it. Compared with the cityscapes of Beijing and Shanghai, Jia Zhangke said, “Fenyang was nothing more than a doll house.”

“About that time pop music started to flourish, a very important feature in the identity of our generation.” The film Platform pays tribute to the first time Jia Zhangke heard Taiwan singer Teresa Tengs song on a short-wave radio. “I didnt realize at the time why her voice touched me.” Later he understood that the songs he heard before were all about “we,” the collective, such as “We are Communist successors,” or “We are the new generation of the 1980s,” while Teresa Tengs lyrics were all about “I,” the individual,such as “I love you,” or “The moon reflects my heart.” “People of my generation were immediately touched by a deeper world emphasizing the immediate and the personal,” said Jia Zhangke.

In 1984 businesses playing videos began to appear in the county town of Fen-yang, and Jia Zhangke frequented them almost everyday. Most of the screenings were of Hong Kong or Taiwan productions, predominantly the kungfu genre. Jia borrowed from the feats he saw on screen to win fights with other lads. By 1991, at age 21, he was in Shanxis capital Taiyuan studying painting, when he passed by a cinema playing Yellow Earth. “From the title I presumed the film wouldnt be interesting,” but he bought a ticket anyway.

Watching the film, he wept. “I could not help myself. The story was unfamiliar, but the endless Loess Plateau, the people on the yellow earth, and a silent family in the dim light of an oil lamp… that was the life I knew. For the first time I saw myself in a film,” he recalled. Before that strange afternoon, Jia Zhangke had no strong impression of Chinese films, thinking “they were what they were.” But Yellow Earth, directed by Chen Kaige and shot by Zhang Yimou, enabled him to see other possibilities within filmmaking. He fell in love with the art form.

Leaving the cinema, Jia Zhangke made a phone call to his father. “I want to be engaged in filmmaking.” His father immediately went to Taiyuan and challenged him, “You are so short! How can you become a film actor?” When he learned that his son wanted to become a film director, he lit a cigarette, and fell silent. Jia reflects, “In most peoples minds, filmmaking is a rarified undertaking transcending ordinary folk. When he was young, my father happened to see a crew on a shoot in Fenyang, and thought it was a thing ‘not fit for average people to do. I did not know how to convince him, because I knew myself to be nothing more than a commoner.” On finishing his cigarette, the father said, “You try it if you want, but you must take responsibility for your own future.” Back home, Jias parents held further discussions, and concluded, “Whether it will work out or not is something we cant really know for a few years.”

A dedication to his father opens the film Platform. “Since I left home I seldom go back and talk to him. We are on good terms, but theres little exchange. He is concerned about me and worries about me still. I want him to understand my spiritual world through this film.” Later, after his father watched the DVD of Platform, he heaved a deep sigh and went back to his bedroom, leaving his son to speculate on his thoughts. “I think he also saw his own life in it, including his lack of understanding where I am concerned. In short, a very complicated feeling,” said Jia Zhangke.

On the Record

At the crossroads, determined to shift to filmmaking, Jia Zhangke began to prepare for the annual entrance examination for higher education. After three failed attempts, he was enrolled in the Literature Department of the Beijing Film Academy. It was 1993, when Chen Kaiges Farewell My Concubine won the Golden Palm Award at the Cannes International Film Festival. “The atmosphere at school was electric after this event; it made students feel more confident,” Jia Zhangke recalled.

Two new Chinese-made films were shown each week on campus in those years. But in many of them the details of the lives depicted were absurd – even the eating habits of an ordinary family were not true to life. “On the dining table of a village cadre were glasses of orange juice and milk, even butter, where you would expect porridge and pickled vegetables. In short, the life shown in these films has barely anything to do with the day-to-day reality in China as far as I know.”

Jia Zhangke finished the screenplay for Platform while was still in college. The plot straddles a decade, and it had to be shot in different locations, meaning the production required a large investment. So he shelved it for a while and made a low-budget film, Xiao Wu, for RMB 200,000 (10 to 15 percent of a standard investment for a China-made film at the time). Released in 1997, it follows the life of a neer-do-well, his values, virtues and love interests.

Xiao Wu is the name of the protagonist, a thief who calls himself a “craftsman.” He struggles in a rapidly changing society, but cannot quite fit in. Around him there are people who adapt quickly: smugglers of cigarettes refer to themselves as “traders,” and prostitutes call themselves “entertainers.” Not prisoners of their own conscience, they can overlook moral responsibility. Jia Zhangkes camera bears down on things as they are, and stokes the burning truth. The film was acknowledged as original but cinema verite – coarse and improvisational.Actually he dramatized the most quotidian of matters, but not for the sake of merely exposing shameful recesses that might cater to the exotic tastes of certain Westerners.

Jia gained inspiration for Xiao Wu on a home visit during Spring Festival, the most important holiday for the Chinese people. As is the custom, Jia returned to Fenyang to be with his family. Sadly, he found that in only a years absence, the deleterious effects of the commodity economy had reached the grassroots of his community. He no longer felt like he knew people. Many old friends no longer contacted one another, some people fell out with their parents after marriage, and some people divorced soon after their marriage. All this social turmoil happened within one year. The film Xiao Wu is how Jia Zhangke reflected on all these changes.

Xiao Wu won awards for independent film production from Berlin, Nantes and Vancouver. As a result, it became easier for Jia to get his projects funded.

Many people admire him for pointing his camera at marginalized groups in the cities, even on the “silent majority,” the socially voiceless. There are also people who disapprove of his work for being focused on what they call the “extreme margins,” and then again there are those who complain that his films are “too close to reality,” documentary in nature, and not truly creative.

In 2008, when shooting the film 24 City, which is about a state-owned factory that is relocated to give way for commercial development, Jia Zhangke was once again determined to reflect real people in real situations. He spent more than one year interviewing workers, and then let certain interviewees just ramble on about themselves, as if making a documentary film. “I just listened to them, never interrupting, arranging postures, or editing, and did not press them to repeat the highlights.” He says he knows the nature of the film is motion, but the best form for expressing the personal is to let people talk. Considering these narratives, long but honest and revealing, he just told himself: “I dont care, I will do it at any price.” Then he added, “Never simplify reality.”

There are also several stars in this film, like Chen Chong (Joan Chen). When casting the parts, he considers an actors life experiences. For instance, Chen Chong played an aged factory beauty who had seen better days, since she herself enjoyed popularity after debuting in the film Xiao Hua, made in 1980.

Many of his counterparts believe Jia Zhangke is good at managing performers, either professional or amateur. And on this he comments, “The key lies in the performer believing the story you tell and the feeling you describe in the character. Otherwise, if the performer thinks the story is outlandish or the feeling unjustified, then he or she has no foundation to bring it to life, and the result is a hollow failure.” In Jia Zhangkes eyes, it is not difficult to communicate with the cast, since “They will identify what rings true in whatever you bring to them, and follow their imagination from that foundation. If there is a big conflict, I think the director should examine his own assumptions. Possibly the trouble lies in you being unable to make your team believe in your ideas.”

Art vs Commerce

As an artist Jia Zhangke finds it a bit worrisome that today films are discussed more in terms of money and marketing, with inadequate attention being paid to the content, characters, plots and images. Film industry insiders are first of all concerned about whether a film makes money and how much. He admits that of course a film should make money, because in the first place, it is an industry, and must adhere to good operations and rational structures, but asserts, “The problem is that ‘behind-the-scenes machinations andbackroom discussions have no place being in the spotlight.”

“Im luckier than most in that I need not spend so much time looking for money now. I have worked with some good producers, who gave me extensive artistic freedom.” The contractual length of the film Platform was two hours and 40 minutes, but the final version ran three hours and 10 minutes. “They knew the film was super-long after reading the screenplay, but said nothing,” Jia remembers, and the comment by the Japanese producer was, “Since the director feels it necessary to use more than three hours to unfold his story, then lets respect his judgment.” Such a length means it is impossible to make it commercially successful – predictably the audiences are not patient enough to stay to the end.

On the other hand, Jia Zhangke doesnt categorically refuse to make commercial films. In his art house release Still Life (Sanxia Haoren), he borrowed elements from the kungfu films of Hong Kong. “I think co-existence, especially co-existence of diversified cinematographic elements, are important and necessary.” In 2010, Jia Zhangke plans to make a commercial kungfu-love story In the Qing Dynasty. However, this will also be a departure from the traditional kungfu genre. Instead of securing victory with their extraordinary physical might, the knights in Jias film will need to adjust to a world where their skills are made obsolete by modern weaponry.

“I want to make different types of films. The past decade has been the first stage of my career, mainly interpreting reality. But I like song-and-dance films and police-and-bandit films too. Many of my interests and ideas are yet to be fully realized,” Jia concluded.

He wanted to create an epic about the common man, to highlight the great changes in the era.

Jia Zhangkes camera bears down on things as they are, and stokes the burning truth. The film was acknowledged as original but cinema verite – coarse and improvisational.

A List of Films Directed by Jia Zhangke

1994: One Day in Beijing (short film)

1995: Xiao Shan Going Home (short film)

1996: Dudu (short film)

1997: Xiao Wu, winner of Alfred Bauer Award (First Prize in the Youth forum) at the 48th Berlin International Film Festival; Best Film Award at the 20th Three Continents Festival of Nantes; the Dragons and Tigers Award at the 17th Vancouver International Film Festival; New Currents Award at the 3rd Pusan International Film Festival; first prize at the 42nd San Francisco International Film Festival

2000: Platform, winner of Best Asian Film at Venice International Film Festival, Best Film and Best Director Award at Three Continents Festival of Nantes

2001:In Public (short film)

2001: The Condition of Dogs (short film)

2002: Unknown Pleasures (included in the contest at the Cannes International Film Festival, heroine Zhao Tao a nominee of the Best Actress)

2004: The World (the only Chinese-language film included in the contest at the Cannes International Film Festival)

2006: Still Life (winner of Gold Lion Award at the 63rd Venice International Film Festival)

2006: Dong, Documentary Award at the 63rd Venice International Film Festival)

2007: 24 City, (included in the contest at the Cannes International Film Festival, winner of Alfred Bauer Award)

2009: Shanghai Legend (Wide-screen documentary film)

2010: In the Qing Dynasty (still in preparation)