China’s Ancient Breweries:A Tradition Thriving in Towns from the Yangtze to Yunnan Province

By staff reporter LI KAI

CHINAS history of making distilled drinks dates all the way back to the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.). Some scholars argue its provenance is more ancient still.

Traditional alcoholic beverages in China fall into two categories – baijiu, or spirits, and huangjiu, or rice wine. Both are made of grains, primarily sorghum and rice. The former is the product of several rounds of distillation, while the latter is directly brewed from the raw materials, and therefore contains less ethanol.

In several provinces breweries have a longstanding reputation. The top-grade baijiu mostly come from Guizhou, Sichuan, Hunan and Shanxi provinces; and no place makes better rice wine than Shaoxing in Zhejiang Province. Since water is critical to the flavour of a brew, most old breweries are located near tributaries in mountainous areas.

Moutai, the National Drink

Maotai (Moutai) Town sits by the Chishui River in Renhuai City in northwestern Guizhou Province. The river rises in northeastern Yunnan Province and empties into the Yangtze River after flowing 500 kilometers through Guizhou and Sichuan, thereby supplying water for producers of a dozen famed liquor brands in China.

Sequestered in a steep valley and traversed by a torrential river, Maotai Town is warm in winter and dry in hot summer, a climate that is congenial for microorganisms necessary for fermentation. The Chishui River is crystal clear and greenish blue, as a result of the rich minerals in its water. Industrial plants are banned in the river area to prevent pollution, leaving the water clean for drinking.

The town of four square kilometers sprawls up the mountain like a huge honeycomb. Buildings, tall and low, huddle on the precious level plots of mountain slopes. Of its population of 20,000, half work for the Moutai Distillery Co., Ltd.

Besides the state-owned Moutai Company, there are 400 to 500 distilleries of various sizes in the town, founded by either former company employees or families of current staff members.

The making of Moutai largely follows traditional techniques, which are no secret in the town, and are therefore used in every distillery. With the same source of water and other materials, all local-made liquorsare of fair quality. But that of Moutai Co., Ltd. stands above the other brands for the precision manifested in every step of the brewing, better expertise in blending and longer storage.

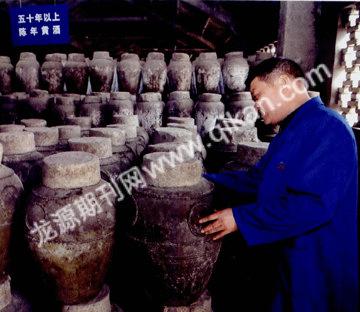

Liquor shops outnumber businesses of any other kinds in the town. Many of them sell bulk liquor, which is contained in big jars sealed with plastic sheeting. Every jar bears a sticker notifying the contents brand and grade. And a notebook on the wall by the counter displays the price for each of them – ranging from RMB 10 to 360 per kilo.

Yu Jican established a distilling workshop a decade ago. Now its annual production capacity stands at 20 tons, and its cellars have expanded from four to eight. Liquor making is a business where returns come slowly: a brew is good for drinking only after being sealed and kept for at least three years. But the good side is a brew will never decay, and instead grows better in taste with the price rising commensurately with its age.

Yibin, a Living History

Yibin in southern Sichuan Province is the spot where the Minjiang and Jinsha rivers converge into the Yangtze River, and hence it merits the title Number One City on the Yangtze.

When people fly to the city, first thing passengers catch sight of on the ground below is a mega-sized bottle of Wuliangye, the second best known spirit in China after Moutai.

The Wuliangye Group in the city operates in two areas, the old production district in the downtown area and a 10-square-kilometer new district in the suburb, known as the Capital of Liquor, which is open to tourists.

The highest spot in the new production district is the Jiusheng (Liquor Saint) Hill, from which people can look down at the worlds two largest brewing workshops and a breathtaking sight of 6,000 fermenting pits at the foot. Beyond them is a 50-meter-tall grain warehouse built in an ancient style. It consists of two rows of 16 colossal white columns sitting on eight platforms and crowned by traditionally designed pavilion roofs. The columns are hollow, and each accommodates as much as 1,250 tons of grain. Next to the warehouse is an ancient pagoda. Below is the century-old Anle (Peace and Joy) Spring, which supplies the factory. A well has been dug at the site, reaching 90 meters downward to the aquifer sustained by the Minjiang River. The gigantic bottle-shaped structure is a complex, its neck forming a water tower, the belly accommodating a power distribution station, and the bottom housing a water pumping station and a test center.

Despite its massive size and a legion of sleek buildings, the new district has yet to produce liquors as good as those from the old district, which comprises a few old workshops scattered around the city.

One of these workshops is Changfasheng in Gulou Street, one of the best-known Qing Dynasty distillers. It now has 30 fermenting pits, two dating from the Ming Dynasty. Other traces of its hoary past include woodcarvings on its wall decorated in traditional patterns of interlocking flowers and a phoenix with peonies.

Another old workshop is located at the sites of the Qing distilleries Lichuanyong and Deshengfu at the northern city gate. It has 27 fermenting pits, three dating from the early Ming Dynasty. Recent excavations prove that they are among the oldest of their kind in China.

The above two workshops of Wuliangye has been making liquors continually for 600 years, the longest period recorded in China. Their fermenting pits are also the oldest and best preserved.

According to historical records, Sichuan Province was the leading liquor producer and consumer a century ago. Liquor shops first appeared in Yibin in the early Ming Dynasty. They retailed what they brewed. By the Qing Dynasty four distillers – Lichuanyong, Changfasheng, Zhangwanhe and Deshengfu – thrived and purchased 12 fermenting pits that had been in operation since the Ming Dynasty.

Today Changfasheng (meaning Long Prosperity) remains a cluster of low, dimly-lit and moth-eaten wooden huts that were built in the Ming Dynasty. A strong smell of lees infiltrates every room, where most work is done manually to ensure the authentic flavor of the drink.

The Wuliangye Group considered moving the old workshops to its new district, but soon found that their products degraded inexplicably in the new location. “There are more than 20,000 fermenting pits in our new district, which are all covered with sediments from the old pits. In addition, we employ modern technologies to replicate the microorganism condition of the old pits. But to our disappointment, the new pits just cannot produce as good qualityliquor as those from the old ones,” said He Yu, deputy chief of the companys old district. “Approximately 40 percent of the yields of the old pits are grade one, but the rate is near zero for new pits.”

Shaoxing, Home of Rice Wine

Rice wine is a beige or brown alcoholic drink. The color is the result of chemical reactions between sugar and amino acid, or comes from caramel.

Shaoxing people prefer rice wine, which is lower in alcohol and mellower. “Good rice wine can be shelved for 10, 20 or 50 years, and itgrows better with the passage of time. But inferior brews have a short life span,” said a local brew master whose favourite is 10-year old rice wine. “After a decade all flavours – sourness, sweetness and fragrance – have fully mellowed and been perfectly mixed and finely soaked by the liquid. Take a sip, whisk it around the mouth before letting it down the throat. Thats real enjoyment.”

Jianhu Lake, 10 minutes drive from Shaoxing, supplies water for all rice wine producers in the city. Regardless of its shrinking size over the past decades, the quality of its water is largely intact. To illustrate the superiority of Jianhu water, Pan Xinxiang, director of Pagoda Brand Rice Wine Co., Ltd., flipped a coin into a glass of water from Jianhu Lake. The glass was full to the brim. The water surface rose, but not a single drop spilled over the brim. Pagoda is one of the few rice wine breweries that still adhere to traditional manual production. Thats why its products have long been ordered by choosy Japanese importers.

According to Mr. Pan, hand-made rice wine excels machine-made brew, because its fermentation is done in natural conditions, overseen by experienced brew masters who closely monitor every step of the process, and make adjustments accordingly.

Gao Xiushui is such a brew master, nicknamed Brew Mind by locals. He started the career as a 16-year-old apprentice and has been in the trade for over 30 years. “Till today I never dared boast that I made the best liquor.” For the water, rice and weather vary year to year. “In a cold winter, the period of fermentation has to be longer, and when temperatures are higher, the time has to be shorter,” Gao explained, adding, “For the past 30 years I cannot remember any year when the temperature was the same as the previous year, so that I could repeat exactly what I had done earlier.” Gao relies on his instinct, attributing every successful year to the “blessing of Heaven.”

Dongpu is a town 30 minutes drive from Shaoxing. It was a brewing center a century ago. Though distillery workshops can no longer be seen today, the tradition of home brewing has continued, and the sight of elders sipping from coarse clay bowls is not uncommon.

Old distilleries have been converted into civil residences, including that of Qing revolutionary Xu Xilin (1873-1907). Stacks of liquor jars still adorn his yard. Every family makes a dozen jars of rice wine every year. They are sealed and stored for one or two years before being served. This milky home brew is free of caramel, but exudes a smell as inviting as those brews manufactured by professional hands.