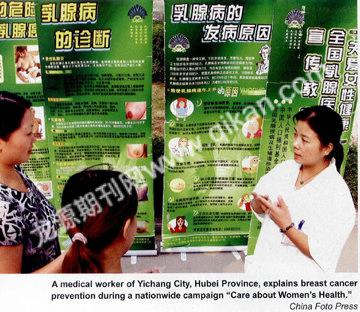

The Plight of China’s Breast Cancer Screening Program

By LI HUJUN

PROFESSOR Xu Guangwei, 74-year-old former chairman of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association (CACA), worked as a surgeon his whole life. He has various regrets, but nothing arouses more complicated feelings than the “Breast Cancer Screening for One Million Women” project that he initiated after retirement.

How Did the Project Start?

On April 21, 2005, when the official start-up ceremony for the breast cancer project was held in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, Gu Xiulian, vice chairman of the Standing Committee of the National Peoples Congress and president of the All-China Womens Federation, and Zhang Meiying, vice chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese Peoples Political Consultative Conference, both delivered a speech to express their support. Other leaders also voiced encouragement.

Xu Guangwei contributed greatly to the projects launch. “I worked as a surgeon my whole life, but in fact few of my patients recovered. Treatment can just help lessen their symptoms or give them some comfort,” says Xu sadly. “However, the situation is that there are more and more cancer sufferers.”

It was the realization of the limitations of cancer treatment that made Xu switched his focus to cancer prevention. He decided to start by conducting breast cancer screenings.

Breast cancer is often referred to as a “woman killer.” An investigation released by the Ministry of Health last April showed that the breast cancer death rate had almost doubled in the past three decades, a growth rate second only to that of lung cancer. Breast cancer screening in Western countries has proven effective in reducing the number of deaths, as early detection greatly improves the chances of effective treatment.

As early as the late 1980s, Xu and his colleagues conducted breast cancer screening trials in Beijing. There were also small-scale screening programs in Tianjin, Shanghai and other cities. However, these projects had common problems, namely old-fashioned examination methods and no long-term follow-ups.

After retiring from his position as director of Beijing Tumor Hospital, Xu and some professional friends sponsored a grand project named “Breast Cancer Screening for One Million Women.” The project intended to select 100 high-quality hospitals nationwide as designated institutions offering four standard mammary gland examinations over six years for 1 million women aged 35 to 70.

At the end of 2003, Xu and other organizers presented a project proposal to Wu Yi, then vice premier of the State Council. In March 2004, the Department of Disease Control of the Ministry of Health gave approval for CACA to start the project.

Disagreements About Examination Methods

To Xus surprise, a great deal of disagreement arose as soon as the project began. X-ray mammography is the most common method of breast examination. Mammograms come in three forms, namely Screen Film Radiography, Digital Radiography and Computed Radiography (CR). Screen Film Radiography is the most traditional method and is quite common in China. Digital Radiography has gradually been popularized and promoted in recent years, but it is still less popular in China than in developed countries because of the higher costs involved. The last method, Computed Radiography, is a new approach whose cost is somewhere between Screen Film Radiography and Digital Radiography.

The screening project organizers adopted CR as their method of choice, and the equipment was supplied by the Kodak Company. However, this choice was questioned by some experts, as they believed CR involved high dosages of radioactive rays, while offering poor diagnostic performance. They argued CR should not be used without associated national regulations and quality control criteria.

Under pressure from critics, the project came to a standstill. Xu felt greatly wronged. “The CR method we used is the most up-to-date, designed only for mammary gland examinations. It is not like ordinary CR,” he argues. He adds that the American Cancer Society had conducted tests and had concluded that the dose of radioactivity was safe and diagnostic performance was adequate.

However, critics still maintained great care had to be exercised in choosing the examination method and conducting quality control measures, as both were essential to the projects success. The US, Britain and some other countries have all promulgated specific regulations and quality control criteria in regards to CR. In contrast, China did not issue national standards on mammogram X-ray imaging quality control until 2007, and these were for clinical diagnosis – not breast cancer screening.

Seeking Private Funds from Hanghua

The biggest headache for the screening project organizers was not the disagreement over examination methods, but a shortage of funds.

Although the project was approved by the Ministry of Health and won support of the All-China Womens Federation, the government never allocated money for it. According to Xu, in 2002 the National Development and Reform Commission was inclined to allocate funds, but the SARS outbreak the following year meant this came to nothing.

Under such circumstances, the project organizers had no choice but to seek capital from private companies. CACA, represented by Xu, signed a cooperation contract with Tianjin Hanghua Technology Development Company, an enterprise with no previous experience in the medical business. The company participated in the project to generate profits, a fact openly admitted by Wang Husen, who was in charge of the investment. He believes it is natural that those who invest will seek profit: “Why else would we do it?” he asked.

Xu claims he set some conditions with Hanghua, such as guaranteeing the quality of the equipment, setting prices below market levels, charging no commission to the hospitals, and the screening data not belonging to Hanghua.

Xu also says that the normal price for breast screening in hospitals is around RMB 400, but those hospitals designated for the project offered a preferential price of RMB 200. Even so, for many Chinese women RMB 200 is not affordable.

As cooperation with Hanghua began, company staff rented an office in the same building as CACA, and started to work in the name of “Breast Cancer Screening for One Million Women.”

Although Xu was the project director, in reality all the work was managed by Hanghua staff. Chang Guisheng, who is the director of CACAs “Breast Cancer Screening for One Million Women” project office, says that company staff handled and controlled everything, from the office seal to daily operations.

Problematic Cooperation

Hanghuas involvement soon created a lot of problems. Most of the equipment the company sold to designated hospitals was purchased from overseas medical imaging companies. Of these Agfa, Planmed and some others claimed Hanghua defaulted on their payments. In November 2007, Agfas credit management consultant Wang Guijuan sent a letter to the Ministry of Health complaining that Hanghua were over two years in arrears on their payments. Even more shocking is the fact that a mobile screening vehicle Agfa donatedin June 2005 to the project is now “missing.”

The vehicle was worth over RMB 1 million. Belgian King Albert II specially attended the donation ceremony while visiting China. However, Chang Guisheng, who has worked on the screening project since June 2006, claims CACA never received the vehicle.

In addition, Chang says that one of the designated hospitals hasnt received receipts for payments made on the equipmentpurchased from Hanghua.

Similar disputes deepened the conflict between CACA and Hanghua. These disputes also resulted in dissatisfaction from leaders in the Ministry of Health. In September 2006, CACA terminated its cooperation with Hanghua.

Disputes Continue

As there has never been a third-party audit, CACA is not clear about the projects income or spending. Hanghua project representative Wang Husen claims the company didnt earn any profit, and in fact lost a lot of money. As for the money earned from equipment sales, he says: “It was all used on project operations.” He also complains that at the beginning Hang-hua expected its investment in developing remote medical consultation software, and other aspects of the project, would bring profits. But the termination of cooperation made it impossible to recoup any investment.

Disputes between Hanghua and an equipment supplier and a designated hospital have also drawn CACA into lawsuits.

At the end of 2007, the CACA leadership was re-elected as office holders terms expired. Hao Xishan, head of Tianjin Medical University, replaced Xu Guangwei as CACA chairman. Professor Zhang Guangchao, current secretary general of CACA, says: “Professor Xu Guangwei started the project with very good intentions. However, he is only an expert in the medical field. He made mistakes related to the projects management.”

“In Taiwan, it is impossible to let business activities mix with breast cancer screening,” says Professor Zhang Jinjian of the College of Medicine at the Taiwan University. “As for conducting breast cancer screening, the government needs to support and offer quality management and assessment.” Since July 2002, women aged 50-69 in Taiwan have had the opportunity to take a free breast cancer screening examination. At present, various institutions in Taiwan are organizing over 10,000 people to take part in a large-scale clinical experiment, the results of which will help decide if the threshold age for receiving free examinations should be lowered to 40.

However, the stagnant mainland-screening project did have some positive outcomes. According to Chang Guisheng, 40 designated hospitals for this project examined 120,000 women. Hundreds of cancer sufferers were detected, mostly at early stages.

The Government Takes Over

After ending cooperation with Hanghua, Xu Guangwei came to understand that government support is crucial in breast cancer screening. Fortunately the Chinese government has gradually realized the importance of cancer prevention. With the Ministry of Finances support, the Ministry of Health conducted some examination projects in certain areas in order to detect early-stage tumors. However, these projects did not start with breast cancer screening, but with cervical cancer and carcinoma of the esophagus.

In March 2008, a project named “breast cancer screening supported by central funds” was finally initiated, carried out by CACA. The project planned to offer free breast examinations to 530,000 women aged 35-69 in 53 counties (districts) around the country. The central government allocated RMB 19.38 million for the program.

Professor Chen Kexin of the Tumor Hospital attached to Tianjin Medical University says that this time many domestic experts were invited to discuss the examination method and to supervise and periodically reassess it. She also indicates that project organizers are hoping to widen participation to 600,000 women, or about 20,000 women from each province.

Local governments of some economically developed areas have also started to invest in breast cancer prevention. For example, the “Double Ribbon” activity has been initiated in Beijing, offering free cervical and breast examinations for women within a certain age range. Chaoyang, Xicheng and Huairou districts are the initiatives experimental areas. Over the next year, the Beijing municipal government will expand the program to include the entire city.

Xu Guangwei has never given up his efforts related to breast cancer screening. He has helped establish a fund especially for breast cancer prevention and treatment. “The operation of our foundation will be fully transparent and the foundation is only for the publics welfare,” he says with a deep feeling.

(Source: Caijing magazine)