Balancing Man and Nature in Traditional Culture

staff reporter HUO JIANYING

IN the sixth century B.C. Confucius visited the philosopher Laozi and had a philosophical dialogue on the banks of the Yellow River, later recorded by his disciples in The Analects of Confucius. Watching the running waters, Confucius was quoted as saying, in a tone of helpless regret, “Things elapse day and night just like this [the running waters].” To which Laozi replied, “Men live between heaven and earth, as an organic part of them. Man is born of Nature, just like heaven and earth… They all begin and end in accordance with the law of Nature.” Laozis answer reflects a fundamental tenet of his philosophy: man is just one of the myriad elements comprising nature, and all elements in nature are equal and should coexist peacefully and harmoniously. This interpretation of the man-nature relationship has influenced Chinese thinking, culture and arts for two millennia.

Tao Yuanming and His Idyllic World

Tao Yuanming (365-427) of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420) is but one example of the many Chinese poets whose work reflects the philosophical outlook expressed in Laozis words. Although a career bureaucrat, Tao found himself constantly at odds with the bureaucracy. In 405, Jiangxis Pengze County received notice that a superior official would soon arrive on an inspection trip. Local officialdom immediately set about preparing a reception – except for the magistrate appointed to his position just 80 days earlier. This was Tao Yuanming.

He continued to work on his files, dressed in his loose everyday attire. One of his subordinates cautioned him to dress formally and wait outside the gate for the officials arrival, to which Tao replied; “Ill not bend and bow to a rustic snob merely for an official post thats worth just five sacks of rice.” He then placed his official robe and seal on his desk and resigned.

During an official career of 13 years, Tao resigned several times, but each time his talent, competence and prominent family background led to him being offered another post. Initially, Tao harbored an ambition to “work for the benefit of the country and the people,” but political infighting and his unyielding integrity never gave him a chance to enact his aspiration. Disappointed with corrupt officialdom, he eventually left the bureaucracy for good.

Tao returned to his hometown, where he enjoyed the pastoral beauty of his surroundings and the unsophisticated, though sometimes demanding, country life. He expressed his heartfelt freedom and ease of mind in one of his idylls, which reads: “Born for the rolling hills, never tuned to worldly pursuits, lost I was in the secular trap for 13 years. A caged bird longs to return to its old woods; a trapped fish misses its original pool…Out of confinement, back I am to meet the embrace of Nature.”

Tao Yuanming left more than 120 poems to posterity, most of them idylls celebrating a harmonious and unsophisticated relationship between man and nature, and beautiful rural scenery. He is still regarded as the father of the idyllist genre in Chinese poetry, and is the styles most successful practitioner. His work exerted a great influence over the Tang Dynasty idyllists who followed in his wake.

Xie Lingyun and

Landscape Poetry

Like Tao, many other disappointedofficials with literary pretensions in feudal China withdrew into the “embrace of nature” after retiring from politics, living secluded lives away from the material world. Xie Lingyun (385-433), a contemporary of Tao Yuanming, was also a talented person from a dynastic family, and like Tao was unhappy in his official career. He often went into the mountains. In fact, Xie was such a mountaineering enthusiast that he invented climbing shoes that became known as “Master Xie Clogs.” The shoes had an indented wooden sole that allowed the attaching of an extra pair of removable soles and heels. When going uphill, the climber could remove the attached sole, and when going downhill, he could put the sole back on and remove the heel.

The Master Xie Clogs were said to be very efficient for climbing and were in use for hundreds of years, as evidenced by poems written during the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties centuries later. For example, a line from one masterpiece by the great Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai reads: “Stepping into the Master Xie clogs, I ascend the mountain via the ladder paved by bluish clouds.”

Xie Lingyun excelled in poetry, painting, calligraphy, history and philosophy, but his greatest contribution to Chinese culture was his poetry, particularly the “landscape poetry” genre he created. Xie was a careful observer, an empathic reader, and a creative and eloquent narrator of nature. His landscape poems, which make up the greater part of his canon, are unpretentious, inspirational and philosophical. They were like a breath of fresh air stirring up the stagnant and ostentatious poetic circles of his time, and had a great influence on later poets, including Li Bai.

Li Bai also loved traveling and admired beautiful landscapes around the country. His landscape poetry often utilizes personification, investing the mountains and rivers he describes with souls.

Li Bai had a particular obsession with Jingting Mountain, which he saw as his kindred spirit, and composed 45 poems about the peak. The best known of these is Sitting Alone on Jingting Mountain, which reads: “A flock of birds flies high/A lonely cloud drifts idly by/Watching one another unwarily/Just Jingting Mountain and I.” The poem was composed in 753, 10 years after Li Bai left his official post in the capital because he would not fall in with the snobbery of officialdom.

After leaving the bureaucracy, Li Bai began a life roaming beautiful mountains and rivers. He revealed his feelings in one of his poems: “You ask me why I dwell in the green mountain/I smile and make no reply for my heart is free of care/As the peach-blossom flows downstream and is gone into the unknown/I have a world apart beyond the Earthly realm.”

Mi Fus Stone Collection

The great calligrapher and painter Mi Fu (1051-1107) of the Song Dynasty was an ardent lover of ornamental stones. A noted stone collector, connoisseur and theorist, Mi Fu related to his stones in brotherly terms, even dressing up and bowing to them. Living and working close to Anhuis Lingbi County, an area famous for producing ornamental stones, Mi Fu stored up a large collection, giving each one a beautiful name. He often disappeared into the room housing his collection and stayed with his stones all day.

Upon hearing that Mi Fus hobby was rendering him negligent in his official duties, a superintendent visited to persuade Mi Fu to abandon his obsession. As his superior talked, Mi Fu produced a series of beautiful stones from his pocket, saying, “How can one resist the temptation of such beauty?” When he took out the third one, the superintendent suddenly exclaimed, “I love them too!” With that he grabbed the stone, jumped into his carriage and rode away.

The Song people loved stones, particularly during the reign of Emperor Huizong, under whom Mi Fu served. The emperor was tolerant of Mi Fu because he too was an art and stone lover. The rulers favorite was the porous Taihu stone, which he transported from the Lake Tai area in the south to decorate his palace in the north. Large pieces of the rock weighed dozens of tons, and when his dynasty collapsed, transportation of supplies for the palace had still not been completed. Some stones were simply abandoned by the roadside en route from Lake Tai to Bianliang (present-day Kaifeng), the Northern Song capital.

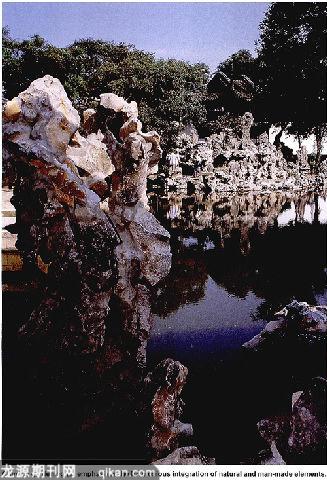

Man-made Landscapes in Harmony with Nature

Stone is an essential element in Chinese gardening, used for pools and stone arrangements. The 17th-century Architecture of Gardening (Yuan Ye) specifies the selection and use of stones in artificial landscapes.

The fundamental principle of traditional Chinese gardening is to “follow the way of nature,” in order to integrate artificial and natural elements harmoniously, a philosophical idea that the ancient Chinese put as the “unity of heaven and man.” In landscaping, this idea requires an architect toalign his aesthetic concepts and pursuits with natural surroundings and elements, such that the man-made landscape looks like a creation of nature.

Architecture of Gardening emphasizes the principle of “making use of what is available.” No matter where a garden is located – by a stream, on a hill, in a field, or near a grove – the pre-existing setting should be utilized and enhanced by clever architecture. The gardening manual extols its own concept of fengshui, stating that, “A garden should not be confined by consideration of its direction, as long as it follows the natural rise and fall of the terrain.” Making use of what is available not only brings the creation of nature into the service of man, but also saves human, financial and material resources.

Architecture of Gardening was written by Ji Cheng, who lived in the chaotic years of the late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Born and raised in picturesque Jiangsu, Ji loved traveling, which took him to beautiful scenic spots in both southern and northern China. This experience provided the background for his later development as an accomplished garden architect.

Disappointed with the decadent Ming Dynasty, Ji Cheng once thought of finding seclusion in the mountains. But, as he later put it, “I had no means to buy a mountain.” Instead he sought to re-create the natural landscapes he loved so much in the gardens he designed. In this way, he made material the philosophical precept of balancing man and nature that has underpinned so much of Chinese culture over the centuries.