Old Businesses Losing Their Last Stronghold

staff reporter LI YAHONG

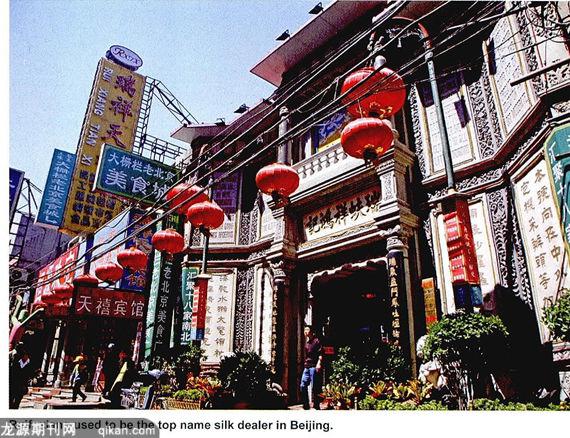

FOR over 600 years, Beijings Qianmen Street has been one of the citys most prestigious and busiest commercial thoroughfares. Just 10 minutes by foot from Tiananmen Square, in the very heart of the city, the 800-meter-long avenue was in its heyday a convergence of more than 100 upscale stores and restaurants, attracting a steady stream of shoppers and sightseers.

Since May 2007, however, the sound of milling crowds has largely been replaced by the din of machinery as an ambitious reconstruction project to restore Qianmen to its former glory has transformed the area into an immense construction site, with much of the street fenced off and shielded from view by painted tarpaulins depicting the neighborhoods projected appearance.

And judging by the scenes on display, it is a future that will have a decidedly international flavor, in keeping with Beijings new status as a world-class destination. In one such illustration, for example, a merchant in a traditional robe calls out to a multi-ethnic crowd of passersby, while in the background ancient architectural masterpieces vie withEsprit and Dior logos for the viewers attention.

That, in essence, is what Qianmen Street hopes to become: a venue with a distinctive national exterior, and a thoroughly cosmopolitan clientele. But it is a transformation that will come at a price as old conventional stores which have been doing business there for decades, even centuries, are displaced during reconstruction, perhaps never to return as rents soar beyond their reach.

The Past and Present

Qianmen, or Front Gate, is actually one of Bejings nine gates leading to the inner city, and it stood apart from the others by virtue of its location along the route taken by Chinas emperors on their annual visits to the Temple of Heaven to preside over grand ceremonial offerings to heaven. The road running southward from the gate gradually became todays Qianmen Street, and as commerce developed over the centuries, it grew into the citys Central Business District (CBD).

According to historical records, already during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) the area was a year-round beehive of people from all walks of life seeking out the wares being peddled by Qianmens army of merchants – all vying with one another in a cacophony of promotional appeals. Beijings elites would visit the street to frequent its many theaters and restaurants, and to see and be seen.

And many of the original stores have survived to this day, including the prestigious traditional Chinese medicine drugstore Tongrentang, which dates back to 1669, the Majuyuans Hattery, in business since 1817, and the shoemaker Neiliansheng, founded in 1853. Others were replaced over the years by a throng of retailers and eateries, which, in a more modern approach, would attract customers with fancy manufactured goods and enticing menus, blaring pop music and “on sale” signs.

What the current reconstruction project hopes to do, then, is to restore Qianmens original atmosphere, so fondly remembered by the older generation. But many locals are skeptical, and doubt that the ultimate effect will be the one being sought.

In a typical remark, one resident of a nearby community, Liu Guixiang, said, “The street will undoubtedly look neat and polished after the work is done, but the ambience that defined the old business district for centuries will be gone.”

And it would seem the concern is well founded. When the street reopens for business in May 2008, the old, venerable stores of long-standing will account for a meager 20 percent of the 180 available spaces, and already those that remain are being contested by more than 1,000 companies.

Understandably, those businesses which have the deepest pockets – many, such as Adidas, Prada, Cartier, Versace and Starbucks, from abroad – will have the greatest chance of securing a prized spot along the avenue, and as a result, most of the former occupants, particularly small family businesses and workshops, will be squeezed out.

Modernization and

Preservation

The steep rent increase is the major obstacle to the return of Qianmen Streets original tenants. With daily rates reaching RMB 37 per square meter, an average floor space of 100 square meters would cost in excess of RMB 1 million per year – a prohibitive sum for most of the smaller vintage stores that operate on slim profit margins.

Among some of these which seem fated to disappear from Qianmen are dozens of the streets well-known snack bars, including Baodu Feng, Yueshengzhai and Xiaochang Chen.

True, in an attempt to save some of the old names, the Beijing municipal government has offered them subsidies of up to 50 percent, but probably it will not be enough.

“Half a million yuan a year is still too much for us,” said Feng Guangju, a third-generation heir to the Baodu Feng eatery, a restaurant specializing in baodu, dishes made with sheep and ox stomachs. “The price for a dish of baodu is RMB 10 now. If we move back to Qianmen, it has to be jacked up to RMB 50, which can drive away even the well-heeled customers.”

Currently, the restaurant leases a space in Jiumen (Nine Gates) Snacks, a collection of booths serving traditional food a few miles north of Qianmen Street. The site is divided into nine sections named after Beijings nine gates, and each is done in a traditional style and adorned with old photographs of their respective precincts.

In one of these, Feng Guangju, 76, prepares baodu in a cramped cabin, handing it to customers waiting outside. “This is all we can do. There is no hope of moving back to Qianmen,” he said.

Baodu Feng is not alone in this situation. The gentrification and remodeling projects that have swept Beijing in recent years have led to hikes in land rents across the city, forcing businesses like Fengs to relocate. For instance, along with Baodu Feng eatery, 11 traditional eateries have found refuge in Jiumen, a small courtyard in a neighborhood of densely packed single-story buildings. Reduced from shops to booths, they no longer have the space to practice the elaborate crafts that once distinguished them.

One of these, the Sheep Head Ma, was known for serving dishes made with mutton from sheeps heads, and was particularly known for the way it prepared them – swiftly slicing mutton into paper-thin wedges with a foot-long knife. The cutting knife, a symbol of the 150-year-old establishment, has been on a shelf since the restaurant moved into the tiny kitchen it was assigned at Jiumen.

Still, not all the news is bad, and about a dozen old businesses in Qianmen have been spared the rent rise problem by virtue of the fact that they own their own land on the street. These lucky few include Qianxiangyi Silk Store, Duyichu Restaurant (specializing in shaomai, a steamed dumpling) and Quanjude, the top name for roasted duck. Zhang, the manager of Duyichu, said: “Our roots are in Qianmen, and it is the best place to experience the old Beijing. We must go back.”

The local residents also look forward to the return of the old stores. “They should return to Qianmen, to which they belong,” said Wang Delu, a 50-year-old resident of the area. “In this regard, the government should offer greater assistance.”

A Bitter Struggle to

Survive

After going through countless ups and downs over the years, the time-honored stores now face unprecedented threats to their continued existence as commercialization and globalization lead to an abundance of commodities and services, and consequently to a greater sophistication of taste among consumers.

“In the past, the old stores were an inextricable part of local life, but no more,” said Liu Manlai, deputy president of the Beijing Commercial Culture Institute. According to statistics from the Ministry of Commerce, only 10 percent of the more than 1,600 businesses with the designation of “Time-honored Store of China” are viable, while up to 30 percent of them are deeply in the red.

Feng Guangju, for one, is disgruntled by the prospect of allowing foreign brand name outlets into Qianmen, whose legacy, he believes, was forged by his forefathers. “The influx of foreigners will dilute the traditional atmosphere of the area,” he said.

But Liu Manlai said the neighborhood has already changed. He cited as an example Ruifuxiang, a silk store founded in 1893. Much of its floor space has long been leased to dealers of a variety of garment brand names. “It was a fad to buy cloth at Ruifu- xiang back when all clothes were hand made. But now, few young people visit tailors.”

Old stores are losing their appeal among younger generations, the leading force behind the modern ethos of consumerism. Western culture has had an influence on almost every aspect of society, including diet, entertainment and aesthetics, as demonstrated by the glittering McDonalds sign at the other end of Qianmen and the young passersby in Nike shoes and fancy hair-dos.

With their new-found spending power, younger people will play a major role in the fate of the old stores, and their tastes are fueling Beijings obsession with the new and modern.

But as Liu Manlai cautioned: “When pursuing development, we should avoid demolishing our traditions and our heritage.”

It is a sentiment that Feng Guangju emphatically shares. “Surely, a middle way is the best course,” he said. A century after his grandfather started the family business on Qianmen Street, he cherishes the hope that he will soon be able to return.