The Changing Life of Farmers:After Working in Cities

staff reporter LI YAHONG

THE village of Xujiawan is a quiet place these days. Except for a couple of old people chatting in front of their homes, there are no young people to be seen. “All the young people have gone, working in the cities to make money,” Wang Lirun, the village Party secretary, said.

The village, located in Guangshan County, in central Chinas Henan Province, is about 1,000 kilometers from Beijing, andmore than 1,000 people, or half of its population, have left to seek work in cities. On average, each sends home about RMB 7,000-8,000 a year.

An Improving Life

Wang Lirun, 59, has been working in village management for 39 years. Farmland is scarce here – only about 0.1 acre per head – and the per capita income is just RMB 1,000 a year. “Before 1990,” Wang told us, “the government gave us 180 tons of grain as food relief every year.But since villagers began to work elsewhere, life here has improved.”

Local governments have encouraged the trend. When farmers leave home to work in cities, they bring back money, skills and new ideas.

“Look at these new houses,” Wang pointed out proudly. The homes are impressive, with tall brick and whitewashed facades. One of the owners is a grizzled old man by the name of Fu Taijiang – hunchbacked and wearing an old coat, with dark, wrinkled hands from a lifetime of labor. He said the cost of his new house, about RMB 200,000, would have been unimaginable to any farmer 10 years before. Old earthen homes are still to be seen, many in poor condition. Several have completely collapsed.

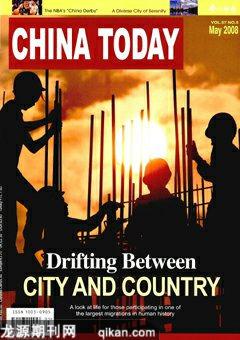

Fu Taijiangs son has been working in Beijing as a construction worker since 1990, and is now a headman, earning about RMB 100,000 a year. Over 200 million farmers like him have left the countryside to work in cities. They work hard and send what they earn back home. In Fu Taijiangs house, the result of his sons hard work is evident: a large bed in the bedroom, and a new television set and refrigerator in the living room.

“Just two granddaughters and I live here,” Fu said. When there is not too much farm work, he gathers firewood for cooking, as he has done for years. The family budget has remained the same, as has his smoking budget: a RMB 3 pack for two days. Their meals are still as simple as ever.

A villager by the name of Xu Maohai was often on the lips of the villagers. By leaving home to work in a large city, Xu is said to have become very wealthy. When he left at the age of 18, he only had RMB 17 in his pockets. But it was the beginning of Chinas period of reform, and Beijing was full of old buildings in need of demolition. After years of hard work, Xu eventually came to own his own company, and by the age of 35 he was worth over RMB 100 million.He was among the luckiest, as many farmers working in Beijing, Guangzhou and Shanghai earn less than RMB 50 or 60 a day laboring for others, growing vegetables or working on construction sites.

“My children work very hard in the cities,” says Fu Fenglan, another farmer. “They come back home just once a year for the Spring Festival.”She has often told her grandchildren to study hard at school, and not become migrant workers in the cities. It is a hard life. Still, she admits that the amount her son makes in the city is five times what he could earn farming at home.

But Fu Fenglan is angry with her daughter for changing her name from Fu Xiaojuan to Fu Xiaolu while working in a restaurant in Beijing. The old name, the girl said, sounded too provincial. Now 22 years old, she left to find work in Beijing when she failed her senior high school entrance exams.

Influence on the Local

Economy

Only children and the elderly are left. Around noon, the village is very quiet, except for the occasional voices of women feeding their children. Two years ago, a young man by the name of Xu Xinbing was elected as village head, but he stayed just one year before leaving. By seeking to work in cities, he changed his life for the better.The locals hoped to find another capable person to lead them, but the task was daunting. “A village head makes RMB 5,000 a year at most,” Wang Lirun said, “far less than working in the cities.”

With so many young people gone, there are not enough hands for farming. Fu Fenglan has just 0.6 acres of land to cultivate, but every year, in a busy season, she has to hire people. Working in cities is not a stable job, and it is very difficult to get a pension and social security. The land back home is their pension.

Local farmers grow rice and wheat, but an acre of land brings no more than RMB 3,600 a year. According to Wang Lirun, however, when some farmers go off to work in the cities, they leave their fields barren, and anyone is welcome to farm them.

The village is in Guangshan County, home of a well-known tea called Maojian. Every village has its own tea plantation, and when the tea leaves are ready, the villagers have to hire women or old people to pick them. Young people are no longer available.

By working in the cities, farmers have changed the look of their home villages. Guangshan County has a population of 800,000. In 2007, about 220,000 people worked in cities, bringing home RMB 1.7 billion. The local government established a development fund for those who brought money back and wished to start businesses.

The county governments work report in 2007 said that investments from those working in cities totaled RMB 1 billion in the last 10 years, and about 32,000 unemployed workers and surplus laborers in the county have found work. In addition to making money, those working in cities have provided experience for those who remain. Now, when looking for work, people are more choosy, unwilling to work far away or take poorly paid jobs.

In 2006, Xu Maohai donated over RMB 500,000 for the construction of a primary school, a pool and the village Party branch office. “The money they brought back,” Wang Lirun said, “is the main source for local development. Many of them have worked in big hotels or modern factories. Some have saved enough money for a small business of their own.”

By working for someone else, Yan Shuangxi, from the village of Yanhe, learned how to make down-padded anoraks. He now has his own business and makes RMB 10,000 a year, he said.

“Life is much better than before,” Wang Lirun told us. “Spending RMB 60,000 or 70,000 to build a new house is common practice. People have become more calculating. Money is involved even among blood brothers when help is given.”

Missing Their Husbands

Having their husbands working in cities means separation. Fu Qianxiu is a farmer in Yanhe. Every day, she works her family plot. Although her husband is away, she never complains. Her husband, Yan Naishun, is 52 and has worked in Beijing for 10 years. “I watch TV for news and weather in Beijing, eager to learn anything that happens there.”

Her village is 1,000 kilometers from the capital. The husband and wife meet once a year during Spring Festival. During the day, working in the fields and doing housework allows her to temporarily forget her loneliness. But the evenings are difficult. She turns on the television at six for anything being shown, as long as it makes sound. The 21-inch color TV seems to be her only entertainment. Her husband gave her a mobile phone, and they call each other every week.

“The last few years were hard,” Fu Qianxiu said, “because we had a son to support through college. Even working for others, education is necessary.”That concern has been a mainstay throughout history. Since the practice of imperial examinations to select officials was instituted in the Sui and Tang dynasties, literacy has been the only means for the poor to change their lives and escape the bondage of farming. To contemporary farmers, the moment their children enter college they became city people.

Chinese villages are often made up of clans sharing the same family name.Still,after several hundred years, family connections become weak, and people from the same village, even if they share a family name, are no longer necessarily relatives. Fu Huixiang, a girl in sixth grade, lives with her grandmother. Their yard is filled with kindling for cooking. The girl has posted her certificate of merits on the wall, with the words “be devoted to studies” written by her in color pens. She only wished her parents, both of whom are working far way in Beijing, knew this. At the mention of her parents, the quiet 12-year-old began to cry, because she can only see them once a year, on Chinese New Year.

The All-China Womens Federation recently issued a report about the situation of children in the countryside when their parents leave to work elsewhere.According to the report, there are up to 58 million such children nationwide. They are paying the price for the explosive economic development of China.

China has a rigid residence permit system, and cities and the countryside are managed differently. Urban people and farmers receive different treatment. While maintaining social stability, the practice has meant that farmers working in cities pay a heavy price. “Thanks to compulsory education in the countryside,” Wang Lirun said, “our children are able to attend school in the countryside for free. In the cities, it would be too expensive for us.”

To Fu Qianxiu, the 10-year separation from her husband has been worth it if her son has become a city dweller. Although children hate to see parents leave, as soon as the Chinese New Year is over, parents rush back to the cities. They need the money.