Excision of malignant and pre-malignant rectal lesions by transanal endoscopic microsurgery in patients under 50 years of age

Dafna Shilo Yaacobi, Yael Berger, Tali Shaltiel, Eliahu Y Bekhor, Muhammad Khalifa, Nidal Issa

Abstract

Key Words: Transanal endoscopic microsurgery; Young adults; Rectal lesions; Benign lesions; Malignant lesions; Radical surgery alternative

INTRODUCTION

The most common gastrointestinal malignancy is colorectal cancer (CRC), with an incidence rate that is increasing among young adults[1,2]. Mortality has also increased in young adults since 2004 (1.3% per year), along with worse outcomes[3,4], but data regarding this population are still controversial[5]. Some studies have demonstrated similar outcomes in young and elderly patients, while others have suggested poorer outcomes in young patients[6,7]. Not much is known regarding the reason why these patients, without any genetic predispositions, develop CRC[8]. Furthermore, young patients tend to present with more advanced stages of disease compared with elderly patients[5,9]. The American National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for CRC screening have recently been revised, and it is now recommended to begin screening at 45 years of age[10]. In Israel, however, routine screening still begins at the age of 50 years[11].

The extent of surgery may be influenced by the age of the patients, with young patients with colon cancer usually undergoing extended surgery[12]. For rectal cancer, the standard surgical technique is total mesorectal excision (TME), either by anterior resection (AR) or abdominoperineal resection (APR). This procedure is usually curative for early-stage rectal cancer but might have a substantial impact on quality of life due to its high morbidity and mortality rates. In fact, there is a 20%-40% rate of adverse events, including urinary and sexual dysfunction, anastomotic leakage, and permanent colostomy[13,14]. Due to morbidity associated with TME, other less invasive transanal approaches have been explored for the management of rectal cancer, including local excisionviatransanal excision (TAE) or transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM).

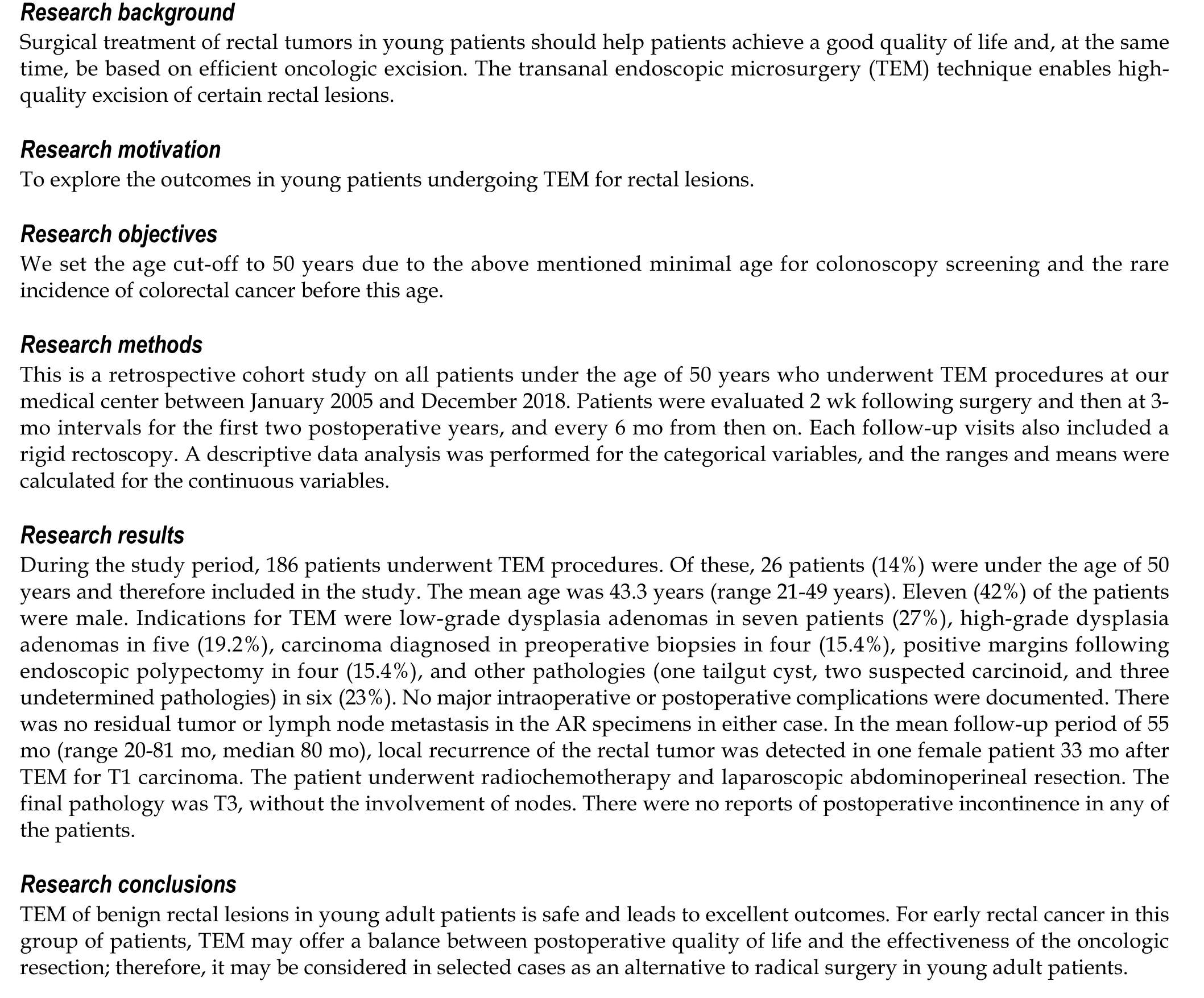

Surgical treatment of rectal tumors in young patients should help patients achieve a good quality of life and, at the same time, be based on efficient oncologic excision[15]. The TEM technique enables high-quality excision of certain rectal lesions[16]. It has proven its superiority over traditional TAE[17] when treating benign rectal lesions, while for early rectal cancer, it has demonstrated better functional outcomes and has excellent long-term survival rates as a form of radical surgery[18].

TEM may be considered the technique of choice for rectal adenoma[19,20] and an acceptable alternative treatment to radical resection in patients with low-risk T1 rectal adenocarcinoma. In elderly and high-risk patients, local excision is considered an acceptable choice for rectal lesions[21,22], but data are limited regarding its application in young adults[23]. The aim of this study was to explore the outcomes in young patients undergoing TEM for rectal lesions. We set the age cut-off to 50 years due to the above-mentioned minimal age for colonoscopy screening and the rare incidence of CRC before this age[5,11].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Rabin Medical Center Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of informed consent. We reviewed the data on all patients under the age of 50 years who underwent TEM procedures at our medical center between January 2005 and December 2018. All data (demographic, clinical, and pathological) were collected retrospectively from our medical center electronic system. These data included the tumor location, tumor dimensions, tumor histology, indications for surgery, operative findings, postoperative outcomes, and complications.

All patients underwent a preoperative evaluation protocol for TEM before surgery, consisting of a colonoscopy that included a biopsy and a rigid proctoscopy defining the number of lesions, the tumor size, its location within the rectal wall, and its distance from the anal verge. Patients with malignant tumors underwent an endorectal ultrasound examination preoperatively.

Patients who had benign rectal lesions not amenable to endoscopic excision, T1 rectal cancer without the involvement of lymph nodes per radiology, or indeterminate margins following endoscopic polypectomy were routinely offered TEM. TEM was also offered to selected patients with retrorectal and submucosal lesions.

Preparation of the patients for TEM surgery and colon resection was the same, with mechanical bowel preparation performed a day before the procedure and administration of prophylactic antibiotics at the time of anesthesia induction.

The details of the technique were previously described elsewhere[24]. All rectal wall defects were closed transversally with absorbable sutures. All patients had a urinary catheter during surgery, which was removed on postoperative day 1, at which point the intake of oral liquid and a soft diet were resumed. Pain control included oral dipyrone, paracetamol, and narcotics. Patients were discharged when oral intake was well tolerated, and no complications were detected, which meant that no unexpected events had occurred during the procedure or in the postoperative period.

Patients were evaluated 2 wk following surgery and then at 3-mo intervals for the first two postoperative years, and every 6 mo from then on. Each follow-up visits also included a rigid rectoscopy. In cases of rectal wall invasion per final pathology of the TEM specimen or unfavorable histologic findings in T1 tumors indicating SM3 or lymphovascular invasion, patients were referred for rectal resection with TME.

A descriptive data analysis was performed for the categorical variables, and the ranges and means were calculated for the continuous variables.

RESULTS

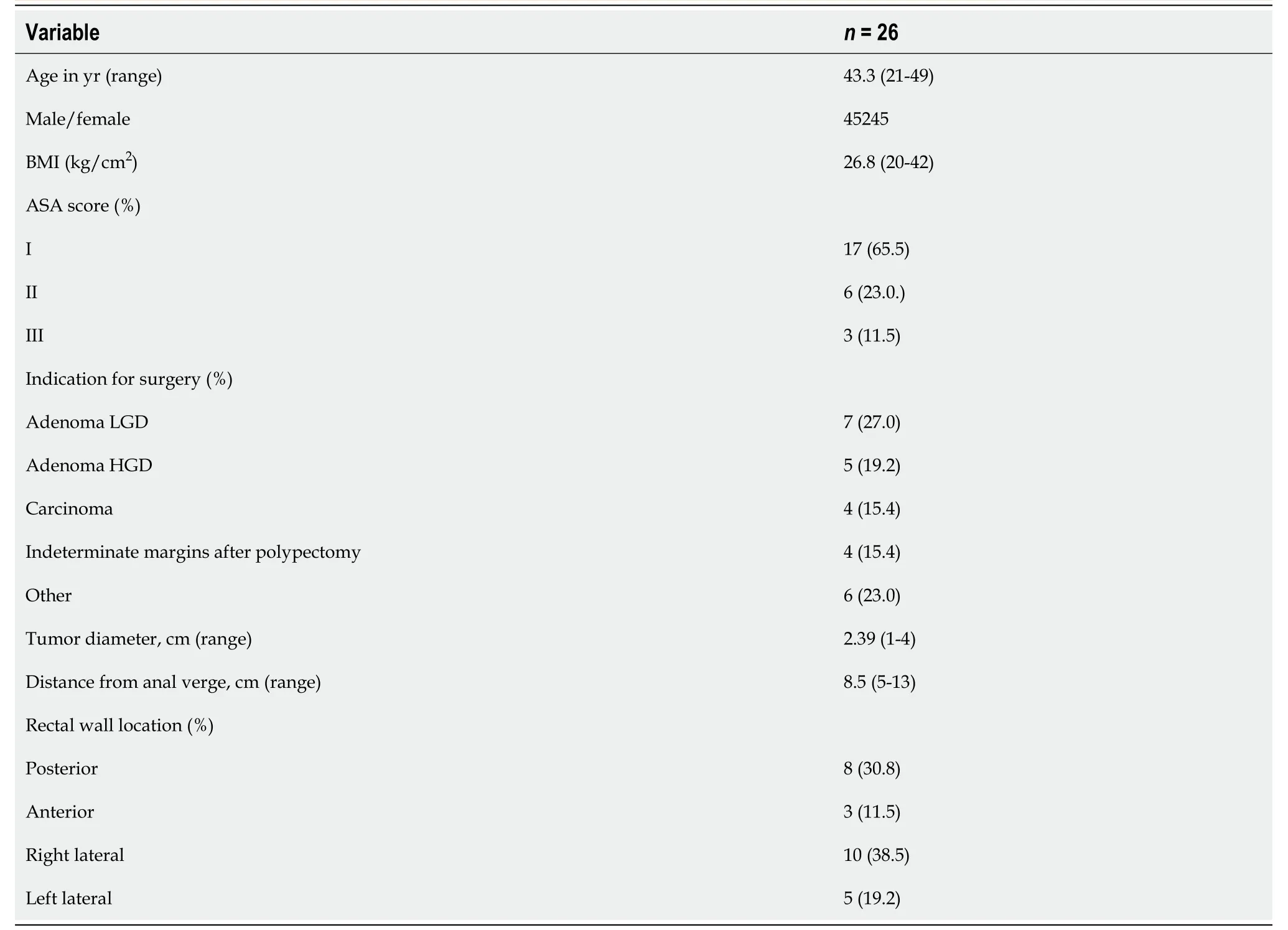

During the study period, 186 patients underwent TEM procedures. Of these, 26 patients (14%) were under the age of 50 years and therefore included in the study. The patients’ demographics and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 43.3 years (range 21-49 years). Eleven (42%) of the patients were male, and the remainder were female. Most patients (n= 17, 65.5%) had an American Society of Anesthesiology score of 1. Indications for TEM were low-grade dysplasia adenomas in seven patients (27%), high-grade dysplasia adenomas in five (19.2%), carcinoma diagnosed in preoperative biopsies in four (15.4%), positive margins following endoscopic polypectomy in four (15.4%), and other pathologies (one tailgut cyst, two suspected carcinoid, and three undetermined pathologies) in six (23%). The mean tumor diameter was 2.39 cm (range 1-4 cm), with a mean anal verge distance of 8.5 cm (range 5-13 cm). Eight (30.8%) of the lesions were located in the posterior rectal wall, three (11.5%) in the anterior wall, and 15 (57.7%) in the lateral walls. Four lesions (15.4%) were diagnosed as carcinomas by preoperative biopsies. The stage of all the tumors was T1 SM1, and all had favorable histological features (i.e., no lymphovascular invasion or perineural invasion).

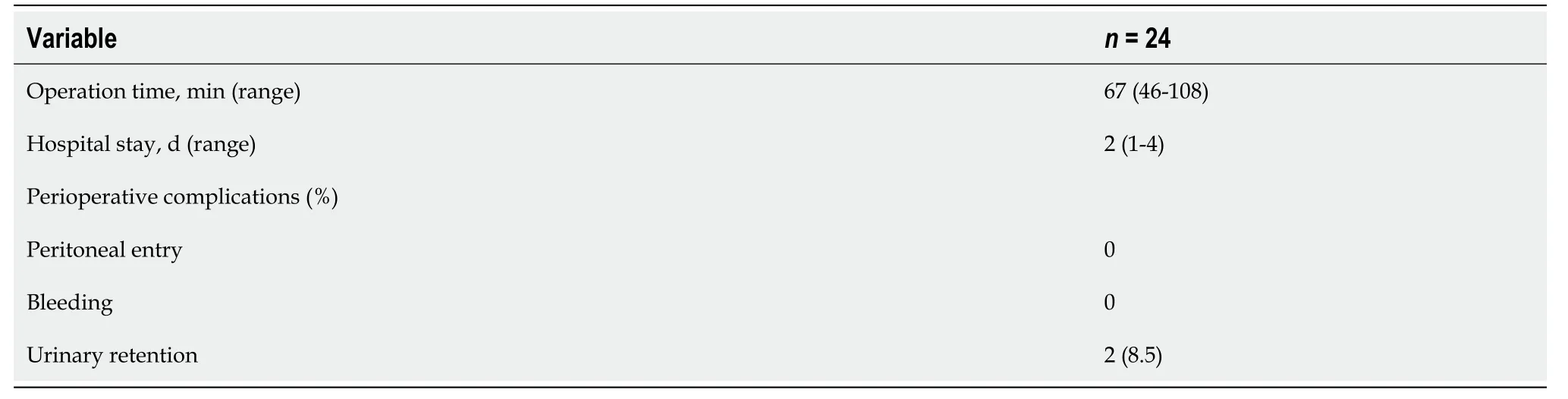

Table 2 presents the perioperative variables. The mean operative time was 67 min (range 46-108 min). No major intraoperative or postoperative complications were documented. The only recorded minor complication was postoperative urinary retention, which occurred in two patients. The estimated blood loss during surgery was minimal. The median length of stay was 2 d (range 1-4 d). One patient was readmitted during the postoperative period (4 d after discharge) due to rectal bleeding; he was treated conservatively with no need for invasive intervention or blood transfusion. No other readmissions were recorded.

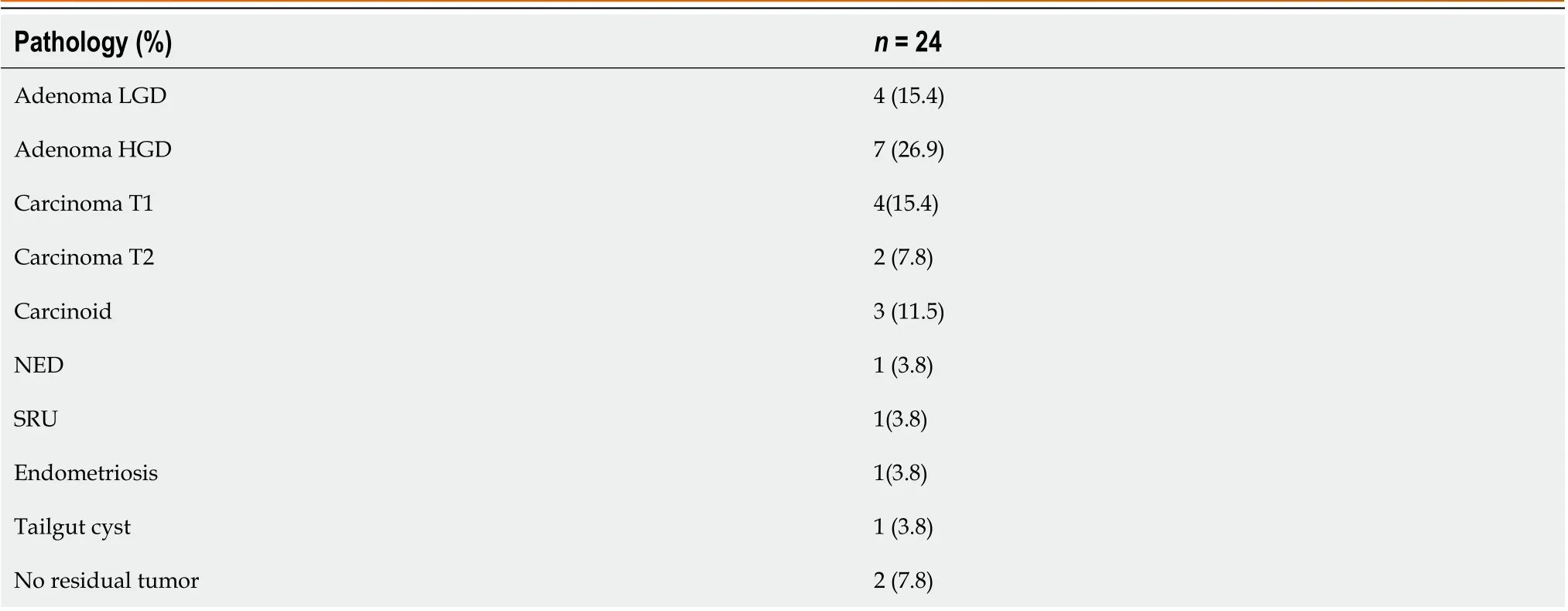

Regarding the final pathological results of the specimens (Table 3), adenocarcinoma was found in six patients, T1 carcinoma in four (15.4%), and T2 carcinoma in two (7.8%). Adenomatous polyps were found in 11 patients (42%), highgrade dysplasia in seven (26.9%), and low-grade dysplasia in four (15.4%); there was no residual disease following endoscopic polypectomy in two patients (7.8%). Other pathological findings included a carcinoid tumor, a neuroendocrine tumor, endometriosis, a tailgut cyst, and a solitary rectal ulcer. Surgical margins were free of tumors in all cases.

In two patients with T2 carcinoma on the final pathology, completion of rectal resection was required; therefore, they both underwent laparoscopic AR 10 wk following TEM. There was no residual tumor or lymph node metastasis in the AR specimens in either case.

In the mean follow-up period of 55 mo (range 20-81 mo, median 80 mo), local recurrence of the rectal tumor was detected in one female patient 33 mo after TEM for T1 carcinoma. The patient underwent radiochemotherapy and laparoscopic APR. The final pathology was T3, without the involvement of nodes.

There were no reports of postoperative incontinence in any of the patients.

DISCUSSION

TEM, like other minimally invasive colorectal surgical techniques, offers an effective treatment option with a low morbidity rate. In high-risk and elderly patients, traditional local excision has been found to be more acceptable for rectal lesions[21,22]. Recently, TEM has been considered by several authors[19,20] to be the technique of choice for rectal adenomas and also an acceptable alternative approach for radical resection in patients with T1 rectal carcinoma with favorable features.

Young patients with rectal lesions are being offered more radical resections, which is a reasonable oncological choice due to their longer life expectancy and the advantages of the radical surgery. However, radical resection in the form of AR or APR has considerable postoperative morbidity rates, and it is therefore rational to choose TEM as an alternative when taking into consideration the balance between the advantages and disadvantages of the radical resection approach[25,26].

Table 1 Patient demographics and clinical variables

Table 2 Operative variables

The overall TEM complication rate for all lesions has been reported to range from 6% to 31%[27]. Possible postoperative complications include urinary retention, suture line dehiscence, and bleeding. In the present study, we reported a urinary retention rate of 7.6% (two cases), compared to 10.8% in the study of Tsaiet al[28]. Neither length of stay nor overall complications were increased in the present study.

As for postoperative incontinence, which is another morbidity to be considered, Cataldoet al[29] found no significant deleterious effects of TEM on fecal continence. Morinoet al[19] noted a temporary decrease in post-procedure anal resting pressure, which returned to preoperative values at a mean time of 4 mo ostoperatively. Our study cohort reported no incidence of incontinence, which is consistent with the reports in other literature[30,31].

The treatment of rectal tumors in young adult patients undoubtedly presents a challenge for the surgeon when seeking to obtain optimal results in terms of both quality of life and oncological outcome. Some studies suggest that the disease is more aggressive in younger adults with rectal carcinoma[32,33]. Others have found no significant differences in oncologic outcomes when comparing young adult patients with rectal tumors adjusted for tumor stage, suggesting that these patients do not necessarily have a more aggressive disease[34].

Table 3 Final pathological results of the specimens

Since aggressive management attempts in young patients with colorectal tumors, such as radical resection, have not resulted in improved outcomes, it is suggested that they be handled in the same manner as older patients, considering the increasing incidence of these tumors among this population[35]. Regarding benign lesions, TEM was found to be more effective than transanal local excision in achieving tumor-free margins[17]. In another study, it also resulted in a less fragmented specimen and was therefore associated with lower recurrence rates[27]. TEM represents an alternative to the transabdominal approach, whereby a benign rectal lesion is situated in the upper rectum, which is especially valuable when considering the high morbidity and mortality associated with the latter approach in all age groups[36], with the possibility of a higher impact in young patients. No incontinence was reported in the long-term results among these patients; however, AR syndrome was experienced in 50%-90% of patients undergoing AR[36].

For malignant lesions, TEM is considered effective and safe when treating certain T1 Lesions without adverse pathologic results and with favorable outcomes. It is more strongly associated with lower morbidity and mortality compared to transabdominal radical rectal resection[37,38].

In our cohort, local recurrence of a rectal tumor was detected in one 49-year-old female patient 33 mo after TEM, who had a flat lesion in the lower rectum. The final pathology revealed a T1 carcinoma without vascular or neural invasion, with free margins. She underwent radiochemotherapy treatment followed by a laparoscopic APR. The final pathologic result was T3N0.

In our series, all T1 lesions were SM1. TEM is currently indicated as a curative treatment for malignancies histologically confirmed as pT1 SM1 tumors. Regarding T1 SM2 tumors, the optimal management approach remains unclear, given that they emerge without any unfavorable criteria due to lymph node positivity. In fact, node positivity increases the level of infiltration of the submucosa, with rates of 1%-3% for nodes in T1 SM1 lesions, 8%-10% in T1 SM2, and up to 25% in T1 SM3[39]. Therefore, we suggest that young patients with T1 SM2 lesions be offered radical rectal surgery, with TEM limited to patients participating in prospective trials with neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment[40].

Two patients in this cohort had a T2 tumor per final pathology and subsequently underwent completion surgery following TEM by radical rectal resection. This approach has been demonstrated to be safe and returned similar oncological outcome to that of primary radical TME surgery. This result was also observed in series where immediate reoperation was performed[41,42]. Laparoscopic rectal surgery following TEM is thus considered safe and has no negative impact on resection completion[43].

For rectal T2 adenocarcinomas, the standard of treatment is TMEviathe transabdominal approach with or without neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy[44], due to the high recurrence rate with occult lymph node metastases[45]. If an unexpected T2 tumor is excised by TEM, it may be managed safely by salvage radical surgery, with good oncological outcomes.

The rate of local recurrence following TEM ranges from 0%-33% for T1 rectal cancers[46]. Stipaet al[47] found that 96% (26/27) of patients with local recurrence following TEM underwent subsequent salvage surgery, nine of whom required repeated TEM, and seventeen of whom underwent radical surgery. In the latter group, the 5-year survival rate was 69%, which is similar to previously reported data[48]. TEM for rectal cancer followed by radical surgery offers an overall good long-term survival rate, which is similar to the rate obtained by initial radical surgery[47]. The risk of recurrence is mitigated by the high repeatability of the procedure, as well as by the satisfactory outcomes seen with salvage radical resection.

In this study, a single case of local recurrence was recorded 33 mo following TEM in a patient with a low rectal T1 lesion who had undergone a subsequent laparoscopic APR with a permanent colostomy. Such patients are more likely to require an APR rather than a low AR, according to some reports, due to secondary scar formation and technical difficulties[49,50]. These technical difficulties, as well as unnecessary APR, can be avoided when choosing the transanal TME technique[51]. While TEM may offer a better quality of life with long-term oncologic safety, it might require a longer period of postoperative follow-up. However, the exact frequency and required length of the follow-up period have yet to be defined, and it is suggested that these patients be treated as “high risk” until further data become available from larger randomized controlled trials.

The limitations of this study include its small sample size, retrospective nature, and various pathologies. There was also variability in perioperative care, as it evolved over the years due to long accrual periods. Furthermore, diagnostic modalities were not uniform for all patients, which may have impacted the choice of surgical approach and the various pathologies.

Local excision by TEM has indeed been interpreted as a successful and valid alternative to the traditional surgical treatment for adenomas and low risk (T1) rectal tumors[25], but it is still considered a compromise, especially in cases of advanced and high-risk rectal lesions, for which TME is considered the standard of care[24]. At the same time, rectal radical resection carries considerable postoperative morbidity, and it is therefore justifiable to offer TEM instead[26].

This surgical approach is likely not suitable for patients with a polypogenic rectum that has several lesions, but they will benefit from an up-front radical resection of the rectum rather than repeated TEMs due to the increased burden and cost of undergoing several surgical procedures.

CONCLUSION

TEM of benign rectal lesions in young adult patients is safe and leads to excellent outcomes. For early rectal cancer in this group of patients, TEM may offer a balance between postoperative quality of life and the effectiveness of the oncologic resection; therefore, it may be considered in selected cases as an alternative to radical surgery in young adult patients.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Shilo Yaacobi D contributed to methodology, original draft preparation, and manuscript review and editing; Berger Y contributed to investigation and original draft preparation; Shaltiel T contributed to investigation and original draft preparation; Bekhor EY contributed to investigation, statistics, and manuscript review and editing; Khalifa M contributed to original draft preparation and manuscript review and editing; Issa N contributed to project administration, methodology, original draft preparation, and manuscript review and editing.

Institutional review board statement:This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Rabin Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Approval No. RMC-0160-18).

Informed consent statement:This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Rabin Medical Center Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of informed consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Data sharing statement:The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DSY, upon reasonable request.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Israel

ORCID number:Dafna Shilo Yaacobi 0000-0003-0553-5664.

S-Editor:Chen YL

L-Editor:Wang TQ

P-Editor:Guo X

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年9期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年9期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery的其它文章

- Preoperative and postoperative complications as risk factors for delayed gastric emptying following pancreaticoduodenectomy: A single-center retrospective study

- Comparative detection of syndecan-2 methylation in preoperative and postoperative stool DNA in patients with colorectal cancer

- Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma using ultrasound features including elasticity

- Surgical management of gallstone ileus after one anastomosis gastric bypass: A case report

- Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion syndrome and its effect on the cardiovascular system: The role of treprostinil, a synthetic prostacyclin analog

- Advances and challenges of gastrostomy insertion in children